The Pollard Miao script is in the fascinating situation of being an endangered syllabary partly based on a different endangered syllabary from halfway around the world.

(Amazingly, this is not unique. The Vai syllabary may have been based on or inspired by the Cherokee syllabary, and the subsequent West African scripts known as the Mende syllabaries—Kpelle, Mende Kikakui, Loma and Bassa Vah—were to some extent based on or inspired by Vai. But let’s get back to the story.)

“The Miao script,” recounts the Unicode proposal, “was created by the Englishman Samuel Pollard, Miao people Wang Mingji, John Zhang, and James Yang, as well as Han intellectual Stephen Lee during 1904 at Stone Gateway, Weining County, western Guizhou Province, China.”

The timing is interesting, even important, because Pollard may well have learned to use the Pitman shorthand system while working in London as a young man, and he certainly knew of the syllabics successfully created in the nineteenth century by a fellow missionary, James Evans, for the Ojibwe and Cree. Both systems would help shape the script that would bear his name.

He arrived in China in 1888 and, like Evans, was keen to meet “aborigines,” the non-Han Chinese highland minorities. He was soon working in Guizhou Province among the A-hmao, a Hmongic ethnic group with a unique language and distinctive culture and traditions. It appears that they had no written language but a rich oral tradition of songs and stories, which included accounts of how they lost their writing. (These will be recounted in my book Writing Beyond Writing.)

Few of the other minority peoples in Yunnan had writing either, but they understood how powerful it could be, given the extent to which they were under the control of the powerful Han administration and Yi landlords.

Perhaps this is why in 1904 a group of A-hmao took the considerable risk of going to see Pollard in the city of Zhaotong. (They usually avoided cities, where they were treated as primitive, despised rustics.)

“They arrived with five day’s supply of food, intent on learning to read, but it does not appear that they sought religion,” wrote R. Alison Lewis in “Two Related Indigenous Writing Systems: Canada’s Syllabic And China’s A-Hmao Scripts,” The Canadian Journal Of Native Studies.

“Was it only for this that they risked the contempt of the city? A few years earlier, a lone A-hmao had ventured into Zhaotong to make contact with Pollard, but left, unable to take the risk…. In the weeks that followed, new groups of A-hmao arrived regularly, staying in the Mission buildings and wanting to learn to read. Within the first month, a hundred eager Miao had visited the mission station.”

Within a few weeks, Pollard and Li Sitifan mastered the basics of the A-hmao language, but neither the Chinese script (which was usually used to write A-hmao) nor the Latin alphabet (the preference of the British and Foreign Bible Society) met the two essential criteria: the recording of the spoken language and the ease with which pre-literate people could learn it.

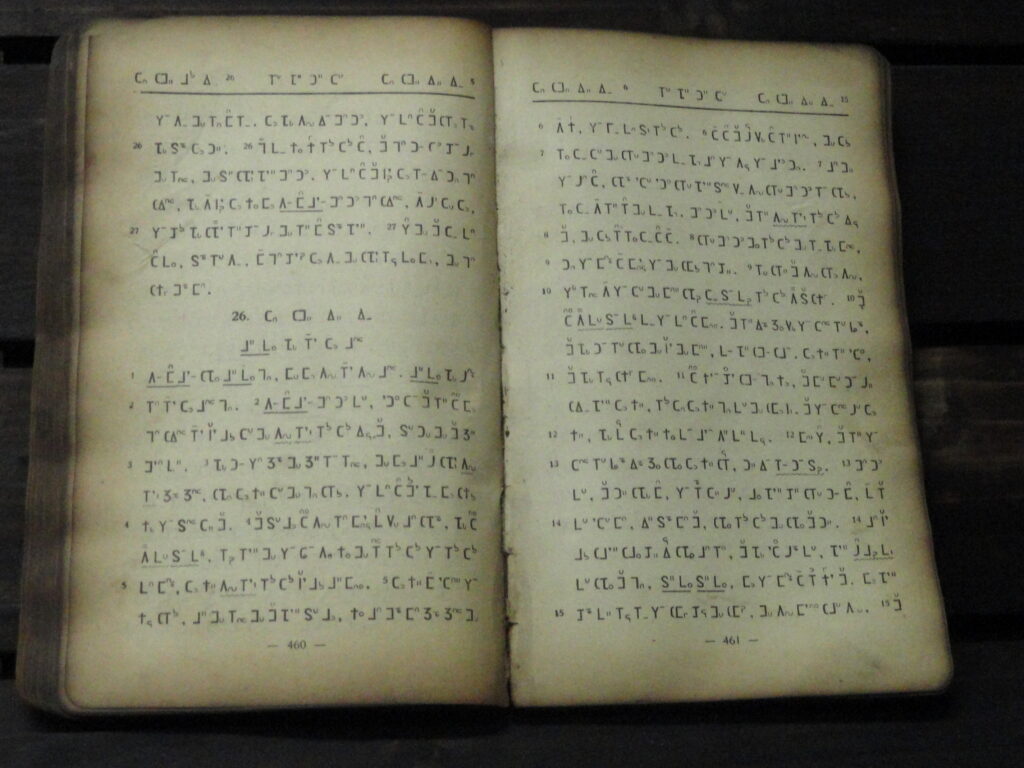

Pollard and Li Sitifan determined to devise a new script for the language, adopting some Cree graphemes, some Latin letter variants, some English shorthand characters, as well as some Miao pictographs. Given the highly syllabic nature of the language, they decided to devise a syllabary that would represent initials (usually consonants) with larger letters, finals (mostly vowels) with smaller letters, and with tones represented by various placement of the small letters relative to the big letter, not unlike the method of the Evans syllabics.

It was a straightforward enough system, ideal for easy learning by a non-literate community, and it was used for several decades, but some Chinese scholars thought that its narrow range of tone positions didn’t completely express the many phonetic tones of the Miao language and didn’t adapt well to Han Chinese loan words. The double letter-size also presented a challenge to typography.

Following World War II and the establishment of a communism, the Chinese government undertook a number of efforts to impose coherence on a vast, disparate and geographically dispersed population in general, and the multitude of ethnic and regional languages and scripts in particular.

In 1957 the Chinese government introduced an alternative system based on Hànyŭ Pīnyīn. This was not popular among the A-Hmao, who preferred the familiar Pollard system.

Various efforts have been made to improve Pollard Miao writing, and a semi-official “reformed” Pollard script has been in use since 1988, along with the older version of the script, and the pīnyīn version.

Given this multiplicity of versions, plus the potential for differences or disagreements between the Chinese government, the Christian church, and the varied and diverse user populations, it’s not surprising that the Pollard Miao script has survived in patchy usage, mainly among its oldest and most traditional users.

It’s hard to know, in fact, to what extent the original Pollard Miao is still in use.

According to Unicode, the Pollard script was originally used by the Northeastern Yunnan Miao, but later, various other Miao dialects began to use it as well, as did some Yi and Lisu, amounting to a total estimated user population of between 200,000 and 500,000.

According to Wikipedia, the Pollard script remains popular among Hmong (Miao) in China, although Hmong outside China tend to use one of the alternative scripts.

In 2009, a Chinese news report announced that a group of Miao gathered at Daqing Village Church in Yunnan Province to celebrate the fact that for the first time in 106 years the Miao people were finally getting the entire Bible in their own language, the article claiming that there are altogether an estimated 200,000 Miao Christians.

A researcher in 2000, on the other hand, was told by local government leaders in the Shimenkan area that in only three “Christian” villages was the Old Miao script known, and then among Christians only.

26.5982° N, 106.7072° E