Profile

The Vai script is a rare bird indeed – an indigenous, non-colonial script that has been accepted, adopted and used to such a degree and over such an extended history that it may be misleading to include it among other endangered writing systems. Certainly, together with N’Ko, it is one of the most successful indigenous scripts in West Africa (that most fertile of indigenous script-creating regions), both in the number of current users and the availability of literature written in it.

The Vai script was created by Mɔmɔlu Duwalu Bukɛlɛ in the 1830s to represent the Vai language spoken by about 104,000 people in what is now Liberia, and about 15,000 in Sierra Leone. Tradition states that while Bukɛlɛ was working as a messenger on a Portuguese ship, he became curious about the written messages he carried. How could the recipients understand the captain’s wishes without hearing his spoken words? When he returned home, he had a dream “…in which a tall, venerable-looking white man, in a long coat, appeared to me saying, ‘I am sent to you by other white men … I bring you a book …’”

(In this respect, Vai is also the first of many indigenous African scripts to have been created in response to a dream; and it is fascinating that while the dream figure commanding the dreamer to create a script is usually a deity, Bukɛlɛ’s could either be a white colonial figure or a white colonial god or a combination of the two.)

According to Bukɛlɛ, the white man revealed a written script that, on waking, Bukɛlɛ couldn’t remember – hardly surprising, as he had no previous experience with the written word. Given this impetus, though, he called in a number of friends and together they created the symbols that made up the Vai syllabary.

In doing so, they may also have been influenced by non-verbal symbols already in use in Vai culture, and possibly by an apparently unlikely transatlantic source: the newly created Cherokee syllabary. In the late 1820s, a number of Cherokee emigrated to Liberia. One in particular, Austin Curtis, married into an influential family and became a chief himself, and he might have contributed to the creation of the Vai script and influenced its form, or simply introduced the idea of an indigenous syllabary into the consciousness of the region.

Vai flourished for a range of reasons that show how important a written language can be, especially for an indigenous people in a time of colonialism.

The circumstances under which the script was introduced are well summed up by Piers Kelly:

“At this time, Vai people and their neighbours were entering a prolonged period of violent transformation. In response to growing racial unrest in the nominally emancipated states of the US, the American Colonization Society secured support for a proposal to resettle vast numbers of freed slaves in an appropriate location in West Africa. Through force, barter and diplomacy, the Society laid claim to a tract of coastal territory just south of British colony of Sierra Leone, and as the new settlers arrived they would displace the Vai and other indigenous occupants from their homelands. Conflict with locals continued to simmer. A mere two years after Bukɛlɛ’s invention of the Vai script, the expanding coastal colony was proclaimed as the nation of ‘Liberia’, a Latinate derivation for a new ‘land of the free’. Like the European visitors who had preceded them, the African-American colonists were Christians who neither spoke the local languages nor followed West African customs. In contrast, the communities along the Pepper Coast were linguistically diverse and while most were nominally Muslim they continued to observe indigenous spiritual beliefs and practices. Out of this collision of culture, religion and language the newcomers were to reproduce the conditions of segregation from which they had fled, for the most part denying indigenous Liberians constitutional rights within their brave new republic. A number of the arriving colonists were literate, and Vai people did not always draw a distinction between black ‘Americo-Liberians’ and the white missionaries who accompanied them, referring to all groups as ‘whites’ or poros.

“Fuelled by the ongoing slave trade in which Vai chiefs were active participants, persistent intertribal warfare overshadowed the otherwise isolated anti-colonial skirmishes with the Liberian colony (Johnston 1906a). In the 1830s, life on the Pepper Coast was precarious as territories were invaded or recaptured and the vanquished enslaved by the victors, or sold to Atlantic traders. Even the epithet Bukɛlɛ, meaning ‘gun war’ is evocative of the conflict in which the Vai were enmeshed. Although the preeminent Vai chief was to renounce his complicity in the trade and form an alliance with anti-slaving patrols, the practice of keeping and selling slaves persisted within Vai society for some time.”

First of all, Bukɛlɛ took on the role that is crucial for any new script to catch on, or any endangered script to be revived: that of teacher. He established schools throughout the Vai-speaking region to propagate his script, which was learned so rapidly and easily (perhaps because it was based on symbols already familiar to the learners) that some scholars have suggested that the rate of literacy among the nineteenth-century Vai was, in some areas, greater than in many areas of the United States and Europe.

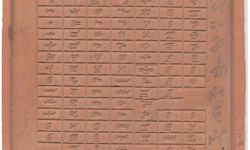

Second, Vai played an important role in trading between the Dutch and Portuguese colonial powers and peoples from the interior of Africa. Brokering exchanges of gold, exotic woods and ivory for salt, tobacco and metals, they had a huge advantage in being able (unlike neighboring tribes) to keep records and create written communications. The Vai syllabary may also have acted as code in the by-then illegal slave trade.

In his article “The Nwagu Aneke Igbo Script: Its Origins, Features and Potentials as a Medium of Alternative Literacy in African Languages,” Chukwuma Azuonye has written: “Basically psychological is the exciting idea of `a script of our own’ which must be used, even against the odds as an expression of cultural independence. In the 19th century, this kind of cultural nationalist attitude seems to have strongly influenced the great popularity enjoyed by the Vai script among the rural population of the Liberian hinterland. As `a script of our own,’ the Vai script served effectively as a medium of indigenous nationalist reaction against the growing dominance of Americo-Liberian elements in the national life of what was then a new African republic. Everywhere in the countryside, outside Freetown, the true indigenes (tailors, foremen, laborers, housewives, market-women, etc) spurned English and the Roman script and insisted on acquiring literacy in their own script, the Vai script, which they called to use in all transactions of everyday life – fabric measurement, recording lists of workers and their wages, market lists, and for personal correspondence and the keeping of family and private personal records.”

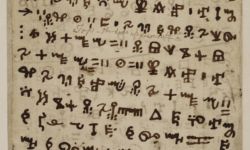

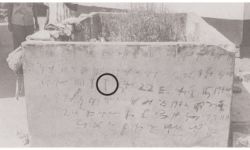

The Vai script was used continuously during each decade of the nineteenth century, but the archives held at Jondu and BandakOro were destroyed in warfare with the neighbouring Gola tribe.

Nevertheless, during the twentieth century, the Vai syllabary was used for writing and publishing clan histories and biblical and Qur’anic translations, and the Institute of Liberian Languages has published several compilations of folk tales and history.

“This trend has continued to a large degree till today with very startling results for alternative adult literacy in rural Liberia,” wrote Azuonye in 1992, quoting statistical research suggesting that as recently as the middle of the 1980s and despite competition with English and Arabic, 20-25% of adult males were literate in Vai, although Vai script was taught outside of formal schooling. One explanation for this phenomenon, he suggested, is that “Since Vai literacy is acquired under informal conditions of instruction, it is most likely that what favors the acquisition of Vai literacy is the meaning it has for those who learn it. Apart from the use of the script to protect business and personal records from the outsider, including the government (which is still regarded in most African countries as inimical to the interests of the individual), the meaning which Vai literacy holds for rural Liberians is purely cultural nationalistic.”

There continues to be a market for Vai literature; it is also widely used in commerce, as well as for newspapers, tombstones and in traditional rituals.

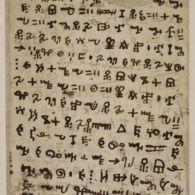

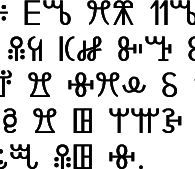

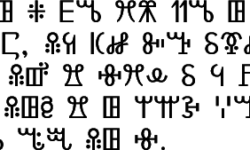

In 1962, the script was standardized at 212 symbols, with every syllable in use being represented by a unique character. Forty or fifty of these characters are in much wider use than the others; many find fifty characters adequate for daily use.

The script remains in use today, particularly among Vai merchants and traders, and in commerce generally. In addition to its presence in commerce, there is a growing body of literature published in Vai: the publication of some small dictionaries, an incubated Wikipedia, a copy of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, and translation of historical sources.

During the Ebola crisis, the Vai script was used to promote health and quarantine regulations, both to display warnings and directives on public signage and to distribute messages among Vai communities.

Moreover, the script is now being taken up by learners who are not ethnically Vai, notably among students at the University of Liberia.

–Edited and updated by Eddie Tolmie.

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General Script, Language, and Culture Resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Unicode (PDF)

- Examining Origins of the Vai Script

- Writing in Africa – the Vai Syllabary

- Scriptsource

- The Vai Script Scholarly Article

- Indiana University Liberian Collections

- Wikitongues Video: Speaking Vai