Profile

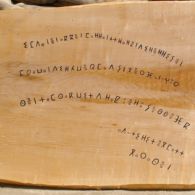

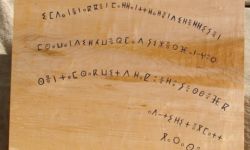

Some of the most extraordinary writing in the world can be seen on the wall of a cave deep in the Sahara.

The site is the open-air Wadi Matkhandouch Prehistoric Art Gallery, near Germa in Libya. It’s startling to find any evidence of human presence in such an inhospitable place, so far from what we think of as civilization. And, frankly, this doesn’t look exactly like what we think of as writing. It’s a meandering string of simple, bold symbols, some of which are more like mathematics than writing. Is that a plus sign? A zero? A percentage sign, for heaven’s sake? Is this writing from the past, or the future?

This twisting strand of language looks so old and so deep it might just be the DNA of writing. And did I mention that the symbols or letters are in such a strange and vivid red pigment that they look as if they’ve been written in blood?

Two thousand years ago, much of North Africa – from Egypt in the east to the Canary Islands in the west, to Niger in the south – was the territory of the Amazigh people. The word means “noble men,” but the Romans gave them the condescending name barbari, meaning “barbarians,” from which emerged the name “Berbers.”

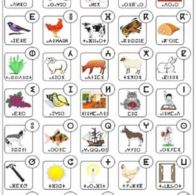

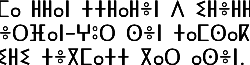

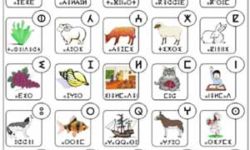

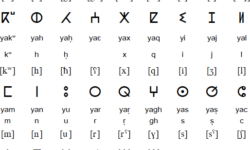

Traditionally nomadic, the Berbers once moved throughout North Africa from the Atlantic to the Red Sea, a region called Tamazgha. One of the languages of the region is still called Tamazight or Tamasheq. The script used to write it is Tifinagh. (Technically neo-Tifinagh, though the Amazigh people don’t use that term.)

The Amazigh coexisted with the Phoenicians and the Carthaginians to such an extent that the early Amazigh script, called Libyque or Libyco-Berber, overlaps with some of the oldest alphabets of the Mediterranean and Middle East. But successive occupations by the Romans and the Arabs meant the subordination of the Amazigh, especially in terms of language. To the Arabic ear, the spoken Amazigh languages sounded, well, barbarous, and as the sacred script of Islam scrolled across the region, Tifinagh fell almost entirely out of use.

Nowadays, after centuries of incursions and colonization, the Berber are scattered throughout Algeria, Libya, Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso. As the other occupants of the region created permanent cities, kingdoms and countries, the Berber people found themselves no longer kings and queens of the desert, but outcasts. They have been subject to a depressing range of human rights abuses, not least in countries which have declared Arabic the official language and have endeavored to suppress or stamp out Berber language and culture.

Tifinagh may be a descendant of one of the oldest scripts in the world. Its name may mean “Phoenician letters,” and Phoenician was the alphabet from which Ancient Greek was developed. And, like Mandaean and Samaritan, it may have survived in something like its original form because it was an outsider language.

In the nineteenth century, new colonial regimes emerged in the region. The official administrative language of Morocco and Algeria became French, with Arabic second and Amazigh actively, sometimes brutally, suppressed – a situation that lasted well over a century.

The Amazigh script was saved by the mountains and the desert. The colonizers’ influence primarily affected the cities and larger towns. Farther inland, the Touareg in particular never stopped using their traditional alphabet, which they called Tifinagh. The women, who were responsible for their children’s education, not only taught the letters but also incorporated them into the distinctive and complex Amazigh tattoo symbols, and into the equally distinctive jewellery, fabric and carpet designs.

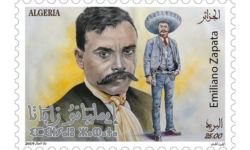

As a result, for the Amazigh, as for dozens of other cultures, writing has an extraordinary depth of appeal and identification, like the head on coinage or on postage stamps, or the colours and design of a flag.

So it was in the mid-1960s that when a group of Algerian Amazigh writers, journalists and activists living in Paris formed the Amazigh Academy to re-establish the Amazigh identity and Amazigh rights in the face of centuries of repression, they decided to reinvent the Tifinagh script (technically, Neo-Tifinagh) as a specifically Amazigh for of writing – and placed one of its characters, the yaz, at the heart of the Amazigh flag.

Today, the status of Tifinagh varies from country to country across North Africa. As recently as 2019, Algeria jailed Amazigh activists for flying the Amazigh flag with its Tifinagh letter. Under the Gaddafi regime prior to 2011, the Amazigh minority in Libya was ranked eleventh worldwide in terms of “people under threat” by Minority Rights Group International.

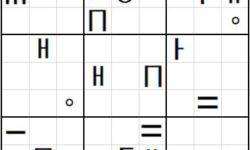

In Morocco, where the situation is better, one of the pivotal steps in the Amazigh revival was the creation in 2001, with government funding, of the Institut Royal de la Culture Amazigh (IRCAM). Ten years before Amazigh became an official language in Morocco, IRCAM was tasked with researching and promoting Amazigh language and culture in seven areas: linguistics, didactics, translation, arts and literature, computer sciences (including the development of free Tifinagh fonts), history and the environment, and sociology and anthropology. IRCAM has published school books in Tifinagh, but the number of trained teachers who speak the Amazigh languages is still very small. In the post-Gaddafi era, similar schoolbooks, posters, CDs and other educational materials have been published in Libya.

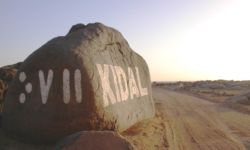

So far, Tifinagh is most visible in signage – at the entrances to schools and government buildings, and outside Mohammed V International Airport. Elsewhere in the Amazigh world, more signage is appearing. Agadez, the largest city in central Niger, added signage in Tifinagh in 2016. More recently, the city of Agadir in Morocco and the town of Nalut district in Libya announced plans to officially include Tifinagh on street signs, and in the near future they will add signage for city and town names, tourist destinations and historic and natural sites.

Amazigh activists, meanwhile, talk of the advantages of a revived Tamazhga, a North African economic union modelled to some extent on the European Union on the far side of the Mediterranean.

Tifinagh is an illustration of the ability of a written language to survive utterly everything: political and military threat, social and cultural change, wind, weather, the biting sands of the Sahara.

Tifinagh may be the once and future alphabet.

–edited and updated by Eddie Tolmie

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General Script, Language, and Culture Resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Tifinagh AncientScripts

- Wikipedia (Berber Languages)

- Scriptsource

- Tifinagh: Learn Tamazight Language

- The Poetics of Tifinagh

- Learn World Alphabets App

- Rebirth of Berber Culture Article

- A dissertation on Tifinagh typeface design

- Tifinagh carving in a sandstone boulder

- Tifinagh inscriptions at the Acacus Mountains in Libya

- Berber Writing: Libyan and Tifinagh

- The medieval village of Chinguetti in Mauritania

- Catalogue of publications by the Institut Royal de la Culture Amazighe in Morocco

- Calligraphy workshop video

- Optical Character Recognition of Tifinagh (project and research article)

Community Resources

Font/Keyboard Resources

Gallery

Sponsor

—Olivier Kaiser