Profile

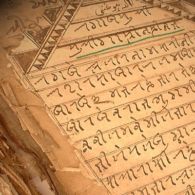

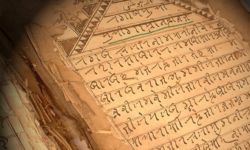

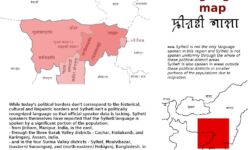

Syloti Nagri may have the extraordinary quality of being a script that is highly endangered in its homeland but is being revived in a different country halfway around the world.Sylot (also written as Sylhet) is now a division of Bangladesh. The traditional story of the origin of the Syloti Nagri alphabet — that is, the script used for the Syloti language — is that it was developed around the beginning of the 14th century by Saint Shahjalal and his 360 saintly companions, most of whom were Arabic speakers. In the late 17th century, Persian became the official language of the Delhi Sultanate and the Perso-Arabic script was used in all official documents, but the Sylheti language and alphabet continued to be used by ordinary people for everyday purposes.

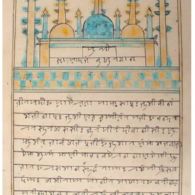

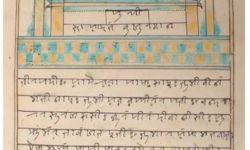

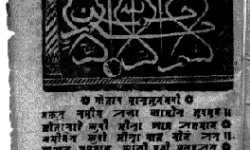

Syloti Nagri enjoyed relatively good health under British rule in India. The first Syloti Nagri print font was made in woodblock in about 1870 by Abdul Karim, who learned the printing trade in Europe in the 1860s. Later, metal typefaces were made using the same design. At least seven presses flourished in Sylhet, Sunamganj, Shillong and Calcutta, printing books and at least one newspaper.

Syloti Nagri was taught in schools in Sylhet until its incorporation into the new nation of Pakistan in 1947, when Urdu was imposed as the new national language. The right to use one’s mother tongue was a major driving force behind the bloody civil war that led to the emergence of the new nation of Bangladesh in 1971-72, but by a bitter irony, the new government established Bangla (Bengali) as the national language, refusing to recognize the mother tongues of the country’s non-Bengali residents.

“Sylotis fully supported liberation from Pakistan,” writes one Syloti publisher. “The general who led the liberation army was, interestingly, a Syloti. The Bengali nationalism suppressed all other languages in Bangladesh including Syloti. It became embarrassing to use Syloti in formal situations. Bangla was considered to be the proper language and the attitude was that Syloti was nothing more than an illiterate person’s Bangla.”

By the turn of the century, one scholar estimated “Literacy [among the nearly 7 million inhabitants] in Sylhet Division of Bangladesh was recorded at 28.2% in the 1991 census. Currently, of those who are literate, the vast majority are literate in Bengali script; there are probably no more than a few thousand who are literate in Syloti Nagri.”

But if the Syloti language and its script were declining alarmingly in its homeland and among the Syloti populations in nearby Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura and Manipur, the emigré Syloti population in the United Kingdom, numbering perhaps 500,000, began supporting cultural revival projects on an impressive scale.

Projects in London and Birmingham published reading primers in Syloti Nagri and trained teachers. After an invitation from the director of the Surma Centre, Camden, London, the School for African and Oriental Studies (SOAS) founded the SOAS Sylheti Project, which has compiled a dictionary for an app, published a storybook in Sylheti, and held an academic conference.

Perhaps by osmosis, there seems to be the early beginnings of a revival of interest in the script in Sylhet, even though it is still not taught in schools. The Ragib Rabeya Nagri Institute, a private institution where the script is taught, reports seeing increased enrollment — perhaps a hundred students a year — and some research and publishing activity.

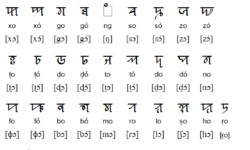

Like several other language cultures, Syloti Nagri also has its own number system, which is not only endangered but is apparently the target of what might be called an active endangerment program.

Marie Thaut of the internationally-renowned School for Oriental and African Studies in London, an expert and impeccable witness, discovered that the original numbers, and references to them, have been deleted in several internet locations. They have been replaced with text saying that Syloti Nagri uses a different set of numerals called Purbi Nagri, which are associated with Bangla, the official language of Bangladesh.

“The original numbers,” she writes, “do exist and shouldn’t be erased from history.”

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General Script, Language, and Culture Resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Unicode (PDF)

- Sylheti Translation and Research

- Wikipedia (Sylheti Language)

- Sylheti Nagri Literature Blog Post

- Scriptsource

- Sylheti Nagri Alphabet Book

- Books in Syloti Nagri

- Books in Syloti Nagri

- An app for learning Sylheti Nagri

Community Resources

- Syloti Nagri Keyboard Facebook

- Sylheti Language Society Facebook

- SOAS Sylheti Project

- SOAS Sylheti Project (Facebook)

- Rongdhonu (Facebook)