Profile

It’s hard to know whether to call Sundanese an extinct script, a living script, or an endangered one — or even all three. Over the past 1200 years, the island of Java has been something of a cultural and commercial crossroads, and the Sundanese language — the Sunda people occupy the western part of the island of Java, and are a distinct culture from the Javanese — has been written in several scripts.

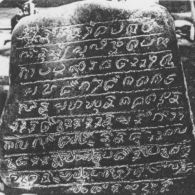

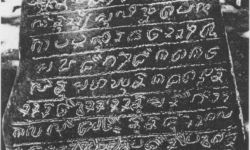

Pallawa was first used in West Java to write Sanskrit from the fifth to eighth centuries CE, and from Pallawa was derived Sunda Kuna or Old Sundanese, which was used in the Sunda Kingdom from the 14th to 18th centuries. At that point Old Sundanese fell into disuse, but importantly (as we shall see), it was the last native script generally used in West Java.

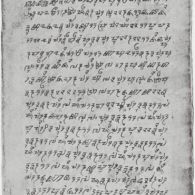

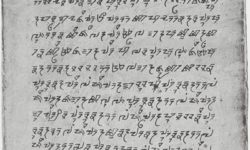

From the 17th century, both the Javanese and Pegon (Arabic) scripts were used from the 17th to 19th centuries and the 17th to the mid-20th centuries respectively, and the founding of the new nation of Indonesia, of which the island of Java became part, brought with it the decision that the official national alphabet would be Latin.

Such was the state of affairs in 1996 when the government of West Java Province announced Peraturan Daerah (Local Regulation) no.6 on the subject of the Sundanese language, literature and script: they were going to choose a script to call their own.

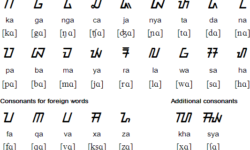

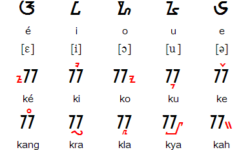

They had five criteria: it should be a script that would work well with the sounds of the Sundanese language; it should correspond to Sundanese culture in terms of both period and area of usage; it should be as simple as feasible; and it should reflect the Sundanese identity.

This was no simple task, and the question was taken seriously. In October 1997, in the main hall of the Japanese Language Study Centre, Universitas Padjadjaran, Jatinangor, a seminar entitled “Lokakarya Aksara Sunda” was held in cooperation with the government of West Java Province and the Faculty of Literature of Padjadjaran University, attended by delegations from local communities and cities in West Java.

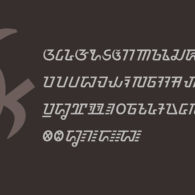

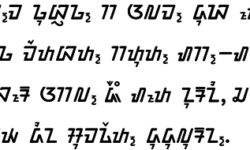

After much discussion, the script that seemed to best fit the five criteria was the Aksara Sunda Kuno, or Old Sundanese script, hitherto to be renamed Aksara Sunda, or Sundanese script, or Sunda Baku (Official Sundanese).

It’s a sign of how sophisticated the discussion was that one consideration was the relationship between the script itself and the tools and materials that had been used to write it. Given that, over the past millennium, Sundanese had been written using stone, metal, skin, leaves, knives, ink, pen, and hammer, should the visual impact of any, some or all of those technologies be reflected in the design of the adopted script?

The outcome represents a very rare attempt by a government to adopt a writing system based on historical cultural identity rather than simplification or convenience.

To date, though, the script has been used more as a display type for commercial, artistic and touristic purposes rather than as the de facto writing system of Sunda. So Sundanese has the strange distinction of being the only native Indonesian script without its own body of literature–though that may change. The Jakarta Post reports that the classic novel The Little Prince has just been translated into Sundanese by Syauqi Stya Lacksana with text in both the Latin and neo-Sundanese scripts.

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General Script, Language, and Culture Resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Unicode (PDF)

- Learn Sundanese Language Video

- iLanguages.org Learn Sundanese

- Sundanese People Background

- Countries and their Cultures Sundanese

- Scriptsource

- Sundanese Print Culture and Modernity in Nineteenth-century West Java

- English-Sundanese Picture Book – Am I Small?

- Writing Tradition Sundanese Article (Indonesian)

- Indonesian literature — history, humour and language

- Information about Aksara Sunda

- An introduction to the Sundanese script in Indonesian.

Community Resources

Font/Keyboard Resources

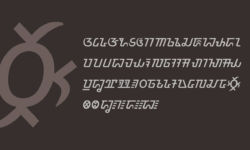

Gallery