Profile

The Osage people suffered a familiar degradation in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: subjugation and forced resettlement from Missouri, Arkansas and Kansas to Oklahoma. Osages who were born in 1906 and later were sent off to boarding schools, where they were forced to abandon Osage and speak English. Most Osages born after 1940, even if they heard Osage spoken around them, spoke English as their first language.

“I grew up hearing Osage spoken all around me,” said Herman Mongrain Lookout, “[but] it never dawned on me to try to learn it.”

The Osage Nation had offered language classes for quite some time—he said the first one he remembers was in 1965. Lookout started learning the language in 1971, when he was 32. At that point there were thirty or forty people who spoke Osage fluently as a mother tongue. “It didn’t take them long to start dying off.”

By the end of the twentieth century there were perhaps only two dozen elderly second-language speakers of Osage. His uncle told him, “Don’t learn Osage. It’s dead. let it go. Go learn Spanish or French, something that’s going to do you some good.”

Yet Lookout—known as “Mogri”–decided to commit to Osage. He could pray in Osage, as he had done so with his father, and with work he could pick up conversational Osage. The biggest obstacle was not in the spoken language, but the written.

“When I first started trying to write down some of those sounds, I ran into problems with it, because every class I went to they never had an orthography… they would say ‘Write it down the way you hear it.’

“Well, I wrote it down all kinds of ways, but when I got home, I couldn’t read it. I never could really nail it using letters of the [Latin} alphabet, because they’re dedicated to the English sound system. You can get close, but you don’t get that Osage sound.”

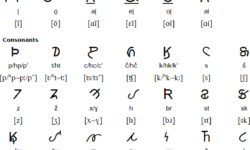

He considered a syllabary, but Osage has 180-200 syllables, which would require a huge and hard-to-learn symbol system. He considered using the International Phonetic Alphabet, or a Latin-based alphabet with a number of added diacritics, as many Native languages have adopted. He even examined Chinese as a possible model.

The way ahead, he decided, was to use not letters but symbols—that is, to use letterforms based on the Latin alphabet, for the sake of familiarity, that shed their English values and stood for Osage sounds.

“I tried to make it look a bit like the English alphabet, but enough like Osage.”

He was facing a paradox: if you create entirely new symbols, you have a unique script that gives a culture’s writing its own identity, but new readers have to memorize them from scratch.

If you use familiar symbols, though, they require a kind of reprogramming of the reader’s mind—not unlike the Cherokee syllabary, in which some glyphs are in fact identical to English uppercase letters, but have entirely different sound values.

He faced considerable resistance, especially from tribal members who felt the new orthography added an extra level of learning at a time when simply keeping the language alive was enough of a challenge.

“Mogri,” one of his colleagues told him, “you’re never going to convince people to do this. You’ll never get them. What you’re going to get is their children.”

And it was true—the younger Osage were more likely to embrace the new orthography.

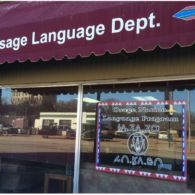

A crucial step in the script’s success was its adoption by the Osage Nation government. In 2004, the 31st Council of the Osage Nation passed a resolution initiating the Osage Language Program. Soon after, Lookout was hired as the director, and was afforded office space in downtown Pawhuska, Oklahoma.

“You need some sort of arbitrary power who will say, `This is official. This is what we’re going to use.’”

After many years of work, the Osage script was accepted into the Unicode standard, and is now available in an Android-friendly font.

Weekly online Osage languages classes are currently offered at beginner and intermediate levels.

“The script is in all the language courses and there are roughly 1100 to 1300 students taking Osage Language courses. They seem to be picking it up fairly easily, and the teachers are doing a good job of teaching it.”

“I think the most important thing about creating an orthography,” said Warren Queton, Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma Language Advocate, “is reclaiming your own identity as people, in terms of the sovereignty of your nation.

“To have an orthography,” Queton said, “is one more tool to say, as Osage people, `This is who we are. This is our identity. This is our language. We made this. We accepted it. We reclaimed it. Now we’re going to carry it on to the future.”

Updated August 2020

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General Script, Language, and Culture Resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Unicode (PDF)

- OsageLanguage.com

- Osage Language App

- Osage Nation Language Department Web Apps

- Scriptsource

- Osage Pronunciation and Spelling Guide

- Introduction to Language and Script