Profile

Nüshu is one of the very few scripts we know about that was created by a woman – or women – and used exclusively by women.

It is not known when or how Nüshu (the word means “women’s writing”) came into being (certainly no earlier than 900), but it seems to have reached its peak during the latter part of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911). The characters, adapted from standard Chinese ones, were used exclusively among women in Jiangyong County in Hunan province of southern China.

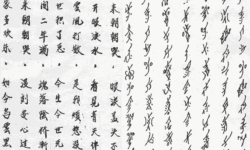

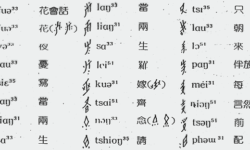

Unlike Chinese, Nüshu writers valued characters written with very fine, almost threadlike, lines as a mark of fine handwriting. The writing was sometimes modified to fit an embroidery pattern, or the individual panels of a fan: concealment was part of its very identity.

This fact underlies almost every aspect of Nüshu – not just because women were not permitted to learn to read and write, but because it was used to capture and communicate aspects of women’s lives that were also personal, private or secret. It is little exaggeration to say that Nüshu represents, both metaphorically and literally, the world of women at a time and in a place when that world was largely invisible to men, and was neither understood nor respected.

One glimpse into this culture is offered by Tan Dun’s multimedia performance work Nu Shu: The Secret Songs of Women, inspired by Jiangyong’s folk songs, mainly the minority (Yao ethnic) music and Sinicized Yao women’s bridal laments.

Tan Dun, who scored the movie Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, spent several years in a remote village in his native province of Hunan, recorded over 200 hours of audio and video and created a work for orchestra, recorded voices and projected images.

Nu Shu: The Secret Songs of Women consists of thirteen movements: “Secret Fan”; “Mother’s Song”; “Dressing for the Wedding”; “Cry-Singing for Marriage”; “Nu Shu Village”; “Longing for Her Sister”; “A Road Without End”; “Forever Sisters”; “Daughter’s River”; “Grandma’s Echo”; “The Book of Tears”; “Soul Bridge”; and “Living in the Dream.”

The featured solo instrument is the harp; the instrumentation is predominantly strings, flute, oboe and percussion, with additional handmade sound effects: water trickling into a bowl, the string players’ bows rapping on their instruments to imitate the snapping of fans.

The music is by turns dramatic, plaintive, reflective, melancholy and grief-stricken, but it is the video images of the (mostly elderly) women singing in Nüshu and the circumstances of their singing that demonstrate its social context, meaning and poignancy.

“Dressing for the Wedding,” for example, sounds like a joyful title until it becomes clear that the wedding would have been arranged, the daughter no more than fifteen years old and the wedding itself possibly the last time the mother and daughter ever see each other.

Nüshu was developed to express emotions that were inconvenient or even unacceptable to the orderly regulation of human life, and as such, these songs represent an entire panorama of concealed emotion. Mothers losing daughters, daughters losing mothers, sisters losing each other – a social web so torn, so desperate, it needed a secret language to bear such emotional weight.

The apparently tranquil, even transcendent “Soul Bridge,” which shows a young woman walking thoughtfully across an ornate bridge, has a sadder undercurrent: this is a bridge where she walks to remember her mother, who might be dead or simply not seen for decades.

The final movement, celebrating the working community of women, provides a cheerful ending, but this, in turn, implies how much that community was needed when those women were routinely separated, sundered, left devastated and facing despair.

After the Communist Revolution of 1949, Nüshu slowly fell out of use as women were granted equal access to state-sponsored public education. At the same time, Nüshu was condemned as a “witch’s script” during the Cultural Revolution, and many texts and artifacts were burned. Yang Huanyi, the last native writer and speaker of Nüshu, died in 2004.

On a more optimistic note, efforts to revive the script are currently being carried out by a few scholars in both China and the West. In 2002, Nüshu was added to the Chinese National Register of Documentary Heritage. A Nüshu museum was built on Puwei Island, Jiangyong County, in May 2007, and at least two typographers are working to create Nüshu Noto Sans fonts. Both are women.

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General Script, Language, and Culture Resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Unicode (PDF)

- Poetic Diary of a Subdued Sex

- Social Studies for Kids Nushu

- Ancient Scripts Nushu

- Introduction to Nushu

- Nushu: From Tears to Sunshine

- Scriptsource

- Gendered Words

- Heroines of Jiangyong

- Star2 Nushu Article

- Women’s Book Dictionary

- This Chinese handwriting is used exclusively by women

- The Last Guardians of China’s Women-Only Script

Community Resources

Font and Keyboard Resources

- Nvshu Sans Font being developed by Chelsy Wu