Profile

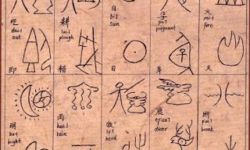

The Naxi people of Yunnan province in China have, astonishingly, two endangered alphabets.One of them, Dongba, has the distinction of being one of only two or three pictographic writing systems still in use today.

According to Dongba religious fables, the Dongba script was created by the founder of the Bön religious tradition of Tibet, Tönpa Shenrab. (The dongba are Bön priests. They play a major role in Naxi culture, preaching harmony between people and Nature. Their costumes show strong Tibetan influence, and pictures of Bön gods can be seen on their headgear. Tibetan prayer flags and Taoist offerings are involved in their rituals.) From Chinese historical documents, it is clear that Dongba was used as early as the 7th century, and by the 10th century, Dongba was widely used by the Naxi people passed down from father to son among the Dongba.

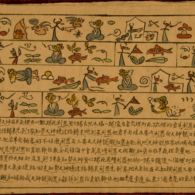

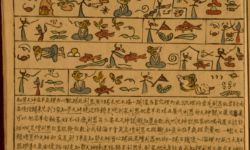

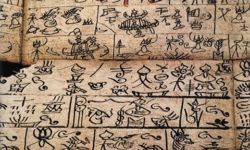

The script is mainly pictographic, and was used in ritual magic, and that in itself suggests something unusual about writing — that one of its root uses was to create symbols that could be influenced and manipulated, and thus by extension manipulate and influence the physical world. A symbol or picture is an extension of the world of ideas or, if you prefer, the world of spirit.

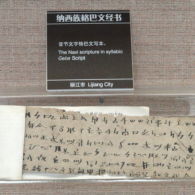

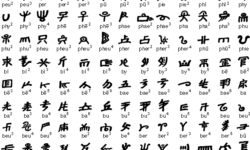

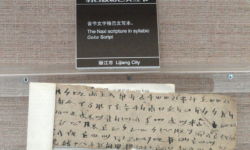

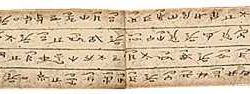

The script was, and is used exclusively by the Dongba, writing originally with bamboo pens and black ink made of ash, as an aid to the recitation of ritual texts during religious ceremonies and shamanistic rituals, of which about a thousand have been set out in Dongba manuscripts. Instead of being a literal text like a prayer book, the Dongba characters serve as a mnemonic, and as such, only key words or ideas are written. This creates a highly subjective script, and means a single pictograph may be recited as different phrases, and likewise different authors may use the same characters to mean different things. Hence the role of the Geba syllabary, which is used as a kind of rubric to clarify the main Dongba text.

Both the Naxi language and the Dongba script have been caught up in China’s turbulent examination and prescription of its own cultural identity. After the Communist victory in 1949 they were discouraged, and during the Cultural Revolution both the Naxi shamanistic practices and their accompanying language were suppressed and many manuscripts were destroyed, some being boiled down into paste to use in building houses. In the 1980s there were official attempts to revive the script in both newspapers and books, but by the end of the decade it was phased out again.

In 2003 UNESCO admitted the Naxi Dongba manuscripts into its Memory of the World Register, commenting “As a result of the impact of other powerful cultures, Dongba culture is becoming dispersed and is slowly dying out. There are only a few masters left who can read the scriptures. The Dongba literature, except for that which is already collected and stored, is on the brink of disappearing. In addition, being written on handmade paper and bound by hand, the literature cannot withstand the natural ageing and the incessant handling. Under such circumstances, the problem of how to safeguard this rare and irreproducible heritage of mankind has become an agenda for the world.”

Yet such a remarkable script has what might be thought of as rebound value — so unusual, graphic and animated it has a life of its own even to those who can’t read it. It has become part of the visual identity of Lijiang, appearing on souvenirs, buses and signage, and some Naxi write phrases in Dongba on their houses as decorations.

Commercial usage is much more common. The signage outside Starbucks, for example, is in Latin, Chinese and what might be called faux-Dongba: the Dongba character for “star,” followed (as there is no character for “bucks”) by a flower-character pronounced as “bbaq” and the dog-character pronounced as “kee,” the whole combination thus approximating to “star-bucks.”

Ben Yang, reporting from Lijiang in 2019, wrote: “It appears that the modern usage of Dongba has some notable differences with traditional shamanistic usage. Firstly, it appears to be far more one-dimensional in character. Shamanistic writings show a two-dimensional layout of signs, with some above and below others. This is not the case in the modern usage, where each sign clearly follows the previous in a linear manner, aligned to a single horizontal (or occasionally vertical) line. Secondly, there appear to be far fewer signs that may be interpreted compositionally. I hypothesize that while Dongba signs may have been compositional, these compositions are now interpreted as atomic (much in the way that Han characters could be interpreted as compositional but are interpreted by users as atomic).

“Note that these differences only apply to novel texts (i.e. business names, modern signage). Dongba murals much more closely resemble traditional shamanistic texts, which may be due to the fact that may be copies of traditional texts rather than novel compositions.”

Today there are about 60 Dongba priests who can read and write the Dongba script. Most are over 70, though at least three are under 30. In an effort to revive the script, the younger Dongbas frequently visit local schools in the Lijiang region to teach classes on it, quite a challenge as there is no universal standard for the script, and to learn all its roughly 1,400 symbols is said to take 15 years of study.

Speaking of which, the University of Geneva, the National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilizations (Inalco, France) and the Beijing Language and Culture University (China) have officially committed, by inter-university agreement, to a unique project–a MOOC to teach the Dongba script. Registration is due to open in March 2023.

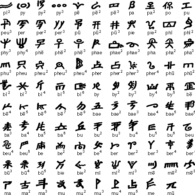

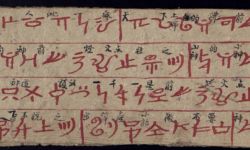

The second endangered Naxi script, the Geba syllabary, may be the only endangered writing system primarily used to transcribe or annotate another endangered writing system. It might even be called an endangered rubric.

While Naxi Dongba script is largely a series of pictograms, the Geba script that accompanies it is a syllabary. As some of the symbols seem to be adapted from the Yi script, and others from standard Chinese characters, it ought to be easier to understand and translate than the Dongba script, but the secondary nature of Geba works against this.

As it is used only to transcribe mantras and annotate Dongba pictographs, rather than existing in full stand-alone texts, it is like trying to understand a script by reading only marginal jottings.

What’s more, the Geba marginal text seems to be highly subjective, or meaningful to a particular priest (or Dongba), and as a result even the phonetic values of the Geba symbols are not fixed. One priest may read a Geba phrase one way, another may read it another.

It’s a great paradox: while the Dongba script enjoys an emerging iconic status in the city of Lijiang even though few people can actually read it, the Geba script–intended to improve comprehension of a Dongba text — is both failing in its traditional duty and falling if anything farther away from daily use and value.

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General Script, Language, and Culture Resources

NAXI

- Omniglot

- Unicode Naxi Pictographic Scripts

- Naxi Pictographic Script Info

- Library of Congress Naxi Article

- Naxi Blog Post

- Ancient Origins Naxi

- Children of the Jade Dragon Book

- Naxi Culture Facts and Details

- China Travel Naxi Ethnic Minority

- Naxi People Information and Resources

DONGBA

GEBA