Profile

If there is such a thing as a formerly endangered alphabet, it might be Meitei (or Meetei) Mayek, used for writing the Manipuri language in the Indian state of Manipur. It is, to a remarkable extent, a rebound script, and as such perhaps a sign of hope for the global movement toward reclaiming cultural heritage and traditional languages, spoken and written.

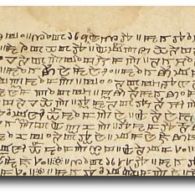

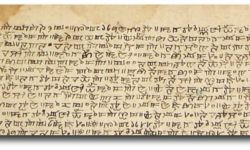

Nobody knows how old the Meitei Mayek script is—estimates range from several hundred years to more than 3,000 — but we know exactly when and why it died.

The script was lost to the speakers of the language when Shantidas Gosai, a Hindu missionary, spread Vaishnavism in the region in 1709. King Pamheiba, who converted, decreed that Meitei Mayek should be replaced by the Bengali script. Accounts differ, but according to the earliest published source, most or all books and documents written in Meitei were burned—such a catastrophic and traumatic event in Manipuri history that even today events and marches are held to commemorate this destruction, which is called Puya Meithaba (The Burning of the Puya, or traditional Meitei scriptures), believed to have occurred on January 23rd, 1729.

After World War II and the tumult of Partition, Meitei scholars began campaigning to bring back the Meitei alphabet. At a writers’ conference in 1976, scholars finally agreed on a reconstructed version of the alphabet with additional letters to represent sounds not present in Meitei when the script was first developed.

When the government dragged its feet, activists adopted extreme methods. Signboards without the Manipuri script were defaced with tar. A plaque at a city flyover was vandalised and the government library in Imphal, which housed a considerable number of books in Bengali, was burned down one night by unidentified protesters.

These guerrilla tactics succeeded: Manipuri language newspapers have to publish at least one news item in the traditional script on their front pages. Hoardings, billboards and other material for public events must also be in the script, and vehicle license plates are undergoing the transition to the Manipuri script.

Publishers with a longer-term view of the market began printing newspapers in the Manipuri tradition, and in English. Most writers have stopped using the Bengali script, while others have rewritten their old books using the traditional alphabet, and one copy of the State Assembly proceedings is recorded in the Meitei script.

Since 2006, students have been taught in the script, creating a new generation of educated Manipuris.

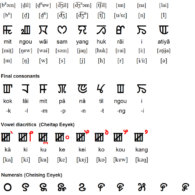

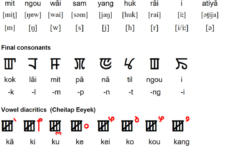

The Meitei Mayek script has a unique built-in learning device: the use of body parts in naming the letters. Every letter is named after a human body part in the Manipuri. The first letter, “kok” means “head,” for example; the second letter, “sam” means “hair”; the third letter “lai” means “forehead.”

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General Script, Language, and Culture Resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Meitei Mayek E-Pao

- Meitei Mayek Learning App

- E-Pao Meitei Mayek Android App

- Manipuri Language Profile

- Scriptsource

- English-Meitei Mayek Dictionary

- Manipuri Transliteration from Bengali to Meitei Mayek

- Meitei Mayek Dictionary at the University of Chicago