Profile

Of all the scripts that are beginning to emerge from near-extinction, few have been as close to oblivion as the Bima or Mbojo script of Sumbawa Island in Indonesia.

Herdimas Anggara writes: “The Mbojo, also known as the Bima or Dompu, live in the lowlands of Bima and Dompu regencies in West Nusa Tenggara province. These two regencies are located in eastern Sumbawa island. There are also some Mbojo who live on Sangeang island. Although this area has a long coast with many bays, most of the population do not make their living from the sea. In fact, most of their communities are built about 5 km from the coast. The northern part of the island is fertile, while the southern part is barren. The Mbojo are also called the Oma (“move”) because they often move from one place to another.

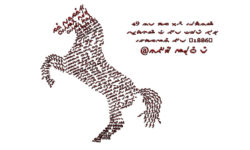

“The main livelihood of the Mbojo is farming in fields, but they also plant rice in paddies using a special irrigation system called panggawa. They are well-known horse tenders as well. Bima women are usually skilled at making plaited mats from bamboo and palm leaves, as well as weaving a famous cloth known as tembenggoli. Many Mbojo live outside their home area and at the same time many outsiders have moved into the Mbojo area. The villages of the Mbojo are called kampo or kampe and are led by a village leader called a neuhi. The village leader is assisted by highly respected village elders. The position of village leader is passed down through the generations.

“The Mbojo are not closed to outside influence. In the past they viewed education as a threat to their cultural traditions, but now they support it from elementary school through university. They view positively outside influences in culture and technology. Modes of transportation include carts or wagons pulled by water buffalo and horse-drawn buggies called “benhurs” after the American film Ben Hur came out.

“Although most Mbojo are devout Muslims, they still believe in spirits and practice forms of animism, even still visiting healers – who are numerous in the area. They ask for advice and help from the healers, especially during times of difficulty and crisis. The Mbojo are afraid of local gods like Batara Gangga (chief of the gods), Batara Guru, Idadari Sakti and Jeneng, as well as other spirit types called Bake and Jin, which live in trees and high mountains. They believe these spirits can bring sickness and disasters. They also believe in sacred trees in Kalate and Murmas, where the god Batara and the gods of Rinjani mountain dwell. The beliefs of the ancestors are called pare no bongi by the Mbojo – belief in the spirits of the ancestors.”

Christopher Ray Miller continues, “Bimanese is a western Malayo-Polynesian language, part of the Austronesian language family of Island Southeast Asia, the Pacific, and Madagascar. Some of its relatives are Malagasy, Malay-Indonesian, Bugis, Cebuano, Rapa Nui, Hawaiian, Maori, Samoan, and the aboriginal languages of Taiwan. According to one theory that has gained some acceptance, Thai and its relatives in southwest China and mainland Southeast Asia also make up their own subgroup among the Austronesian languages.

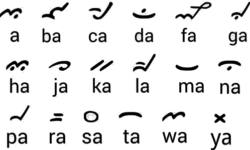

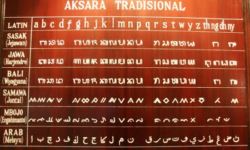

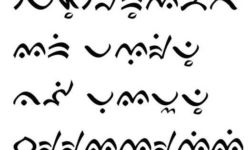

“The Bimanese script descends from the Bugis-Makasarese script of southern Sulawesi together with nearby Satera Jontal, also on Sumbawa, and Lota Ende on Flores to the east. These are all closely related to old scripts of the Philippines and Sumatra and, further afield, northern India.”

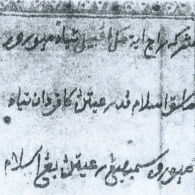

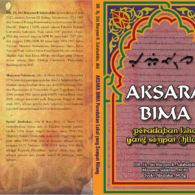

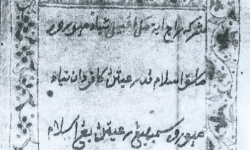

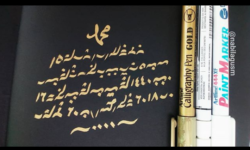

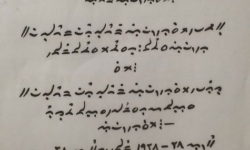

With the arrival of Islam, starting in the seventeenth century, and the gradual adoption of the Arabic script, Bima writing almost completely ceased. A research team studying a palm-leaf manuscript in Bimanese wrote up their findings in a book entitled Aksara Bima, peradaban lokal yang sempat hilang—that is, Bimanese Script, a local civilization that disappeared.

In 2017 a visiting linguist reported, “I wouldn’t even call this an endangered alphabet; it appears to be extinct. It has only very recently gained more interest, but I doubt that the layman in Bima would know about the existence of the script. When I was in Bima, I never saw any such writing on a board or building, which is usually the case in Indonesia for indigenous writing systems.”

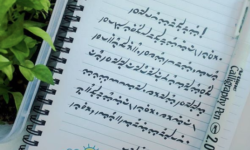

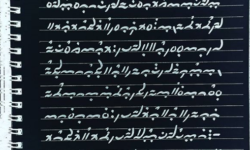

Recently, a newly-formed team aimed to do a study of this script, consisting of Munawar Iwan, Syukri Abubakar and led by the late Maryam R Salahuddin (a descendant of Sultan Bima). With the support of the Aksara di Nusantara community, they have been trying to revive the traditional Bima script found on the royal manuscripts, and they recently developed a Bima font and a Facebook page Tanao Aksara Mbojo Page (in Bimanese this means: “Learn Bima Script”) to pass on information about the script, its history, and photos of old manuscripts that, among other things, demonstrate that the ancient Bimanese script did, in fact, exist.

In early 2023 the organization Tanao Aksara Mbojo Bima announced via Facebook that they had been contacted by a representative of the Department of Education of Youth Culture and Sports of Bima Regency to develop a curriculum for elementary and junior high school students in Bima Registry that would include the teaching of Akara Bima. They have also written textbooks for grades IV and V elementary school classes, which are to be published soon.

“Hopefully by teaching the Bima alphabet in elementary / SMP in Regency / City of Bima and Dompu, the Bima alphabet will be more known and more glorious and fluttering.”

Update June 2023:

“In 1987, after a long research, Hj. Siti Maryam R. Salahuddin (namely the daughter of the 14th Sultan of Bima, Sultan Muhammad Salahuddin) found records of the Bima script at the Indonesian National Library in Jakarta, namely a document by a Dutch researcher, H Zollinger and also records of the Bima script from Raffles in his book History of Java . These two figures are known to have traveled and researched in Bima. Only a few records containing the Bima script have been found, including those found in the Samparaja Bima Museum and the Indonesian National Library. …“The Bima/mbojo script was declared on July 28, 2007 at the closing ceremony of the XI Archipelago Writing International Symposium held in Bima. However, further research must be carried out to reveal all the mysteries regarding the Bima script. So a research project was formed by Hj. Siti Maryam R. Salahuddin, Munawar Sulaiman and Syukri Abubakar to study and research the Bima script on an ongoing basis.“Intensively discussing steps to preserve the Bima script, this month (September 2018) several Bimtek Bima/Mbojo Scripts have been held by the Bima City Education Office. After that the delegation from Bima departed for Mataram to prepare local content designs containing the Bima script which will be taught in 2019.”

Bima appears to be making a comeback, albeit locally and gradually. Another resource is the Tanao Askara Mbojo Bima Facebook group, containing scores of photos of multiple recent conferences and conventions dedicated to the promotion of the script.

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General Script, Language, and Culture Resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Dictionary App for Mbojo

- Bimanese Alphabet Background

- Scriptsource

- Writing Tradition Article on Bima

- App for Mbojo Scriptures