Profile

Mandaeans may have the most fascinating alphabet in the world, a mystical system in which every letter has its own secret meaning and is part of a larger sacred whole.

Until recently, the greatest single concentration of Mandaeans, a non-Arab people whose lineage may go back to ancient Babylon, was located to the south and east of Baghdad. This group faced varying degrees of isolation and harassment under the regime of Saddam Hussein, and many left for other countries in the region (and, to a lesser extent, Sweden, Australia and the US).

The US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, however, served only to make their situation much worse. As law and order broke down, Mandaeans (along with other minority groups such as Assyrians and Armenians) suffered at the hands of both Shiite and Sunni groups, reporting murders, rapes and kidnappings — the last an especially common form of violation because Mandaeans are renowned goldsmiths.

In the face of these assaults (against which Mandaeans were powerless, being forbidden by their faith to carry weapons), nearly all of the 60,000 Mandaeans living in Iraq have fled into a global diaspora.

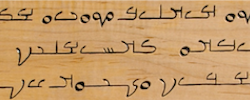

This grim story is all the sadder because of the extraordinary nature of Mandaean culture and the Mandaic script.

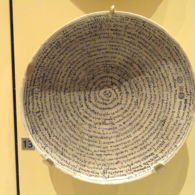

The Mandaeans consider their script to be as sacred as their literature. Like several other cultures, they see writing as such an exceptional gift that it could not have been invented by mere humans – it must have been divinely created and given to them. This, in turn, means that writing – the script itself – is divine, and its forms and practices need to be preserved as they are and always have been.

In a writing-creation myth, the divine creator himself, known as the Light King, sees writing for the first time and is so impressed and astonished he utters: “Who created these [letters]? I did not, therefore there must be one mightier than I!” In other words, writing must have been created by a divinity mightier than the one who created the world itself.

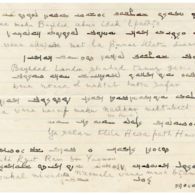

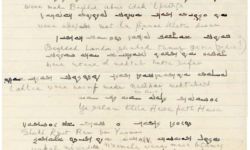

The fact that the script of the modern manuscripts is not appreciably different from that of the earliest manuscripts illustrates how faithfully the Mandaeans have transmitted their sacred literature across the centuries.

Given that the earliest Mandaean writings are perhaps 1,500 years old, that’s amazing. In English, handwritten manuscripts even from the early nineteenth century are noticeably different from today’s writing; anything even older (say, from Shakespeare’s time) is very hard to read.

This faithfulness is also an indication of the Mandaeans’ sense of the importance, even sacredness, of the written word per se.

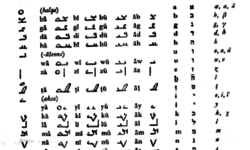

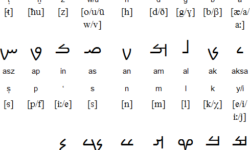

In Mandaic, each individual letter has its own mystical meaning. Moreover, the alphabet consists of Mandaean versions of the twenty-two separate functional letters of the Aramaic alphabet; but it then adds on another two letters to make a total of twenty-four – the number of hours from sunset to sunset and, therefore, a mystical number. One of the added letters is a ligature of two characters, something like an ampersand in English; the final letter is simply the first letter, repeated, to give the impression that the alphabet is not linear and finite but, like the day, repeats after a cycle of twenty-four units. A mandala of an alphabet.

The Mandaean text The Thousand and Twelve Questions tells us that each letter of the alphabet emanated from the last, starting with the circular A, the wellspring (aynā) from which all the letters emerged, to the letter B, and from the letter B to the letter G, and so forth, until twenty-three came into existence. Each praised and worshiped its predecessor, until they formed a new kind of structure – a wall spreading out to the left and the right from the L, the middle letter, because the L is the builder’s clay (or lebnā) that holds the left wing and the right wing of the wall together. Unfortunately, this wall stood only for itself, and could not support anything else, because the right and the left stood apart from one another.

They soon realized that if they were to clasp their hands together and form four corners joining back to the letter A, they could build a solid foundation. Thus, A became both the wellspring from which they emerged and the crown atop their heads. Only then did it become possible to name all things and speak every mystery, because language is not possible without this indivisible republic of letters.

This indivisible republic of letters – an astonishingly rich phrase – shows us how much we take writing for granted and fail to give it its due. The Mandaic alphabet invites us to think of writing as a miraculous transaction, analogous to the act of creation itself. In creating the physical universe, according to many traditions, the creator took a thought, something invisible and insubstantial, and made it visible, solid, habitable. Likewise, the act of writing takes an invisible, insubstantial thought and makes it visible, available to all – in a sense, habitable.

The point, then, is not that Mandaic writing, surviving as well as it can scattered across the world in small, dedicated pockets, is a vehicle for transmitting information that can lead to enlightenment – it’s that each word, each letter, is in itself charged and radiant with enlightenment.

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General Script, Language, and Culture Resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Unicode (PDF)

- GitHub Mandaic Script Summary

- Introduction to Mandaic Lecture

- The Eyes Encyclopedia of Knowledge

- Scriptsource

- Mandaean Scriptures and Fragments

- Comparative Lexical Studies in Neo-Mandaic

Community Resources

Font/Keyboard Resources

Gallery

Sponsor

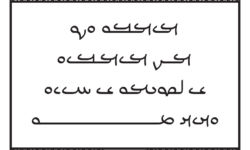

“The Light King said, ‘Who created these [letters]? I did not, therefore there must be one mightier than I!'”

—Chuck Haberl