Profile

It’s easy enough to see how a colonial authority may suppress the identity, the activities, the self-respect and the spirit of the cultures it colonizes.What is less obvious is that colonial powers often employ a divide-and-conquer strategy that leaves indigenous cultures fighting each other.

Even more subtly, colonizers or occupiers tend to want to deal with subgroups they see as familiar or friendly — resulting in a system or privileges and preferments that may be perpetuated for centuries.

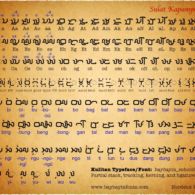

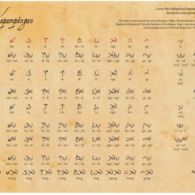

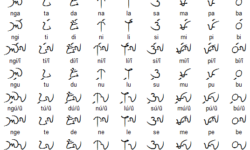

A case in point is Kulitan, a script used for writing Kapampangan, a language spoken mainly in central Luzon. The script, probably one of a family of scripts that arrived in the islands from south Asia, predated the arrival of the Spanish by as much as 200 years. As such, it also predated the Philippines as a construct, for the word and the idea are a colonial creation, a grouping of possessions that had previously been separate entities, renamed after a Spanish king.

“Long before the idea of a Filipino nation was even conceived,” wrote Michael Raymon Pangilinan, a Kapampángan cultural advocate, “the Kapampangan, Butuanon, Tausug, Magindanau, Hiligaynon, Sugbuanon, Waray, Iloko, Sambal and many other ethnolinguistic groups within the archipelago, already existed as bangsâ or nations in their own right. Many of these nations formed their own states and principalities centuries before the Spaniards created the Philippines in the late 16th century.”

The Spanish not only collectively lumped all the islands and their various ethnicities and histories (including their languages and scripts) under a convenient and centralized single identity — by situating their new capital, Manila, in southern Luzon, they created a de facto preferred status on the language of that region: Tagalog.

Tagalog flourished so well under colonial rule that it survived a switch in colonial occupation: under Manuel Quezon, president of the 1935 Philippine Commonwealth under U.S. Occupation, the idea of a Filipino Nation based on Tagalog was conceived. From then on, anything “Filipino” and “national” was understood to mean “Tagalog.” English and Spanish were considered official languages under the Constitution, but Quezon and his cabinet however secretly prepared for the creation of a Tagalog-based Filipino nation should they gain independence during their term.

Tagalog gained official status under yet a third occupation: that of the Japanese. In 1943 the Japanese promoted its use over English so that the Filipinos would, as in the words of Prime Minister Tojo Hideki, “forget their mistaken Americanism and return to their Great East Asian roots.”

“Like the American colonisers,” Pangilinan pointed out, “the Japanese thought that Filipinos are just one people with one language and culture and all other indigenous languages were just mere dialects.”

Under these circumstances, it is hardly surprising that the other languages and scripts of the islands languished. Kulitan, in fact, became a medium of protest.

The script was revived and revitalised by Kapampangan writers led by Aurelio Tolentino to write anti-Spanish propaganda during the Philippine Revolution of 1896, and anti-American propaganda during the Philippine-American War and in the early years of US occupation.

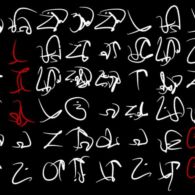

More recently this anti-colonial role was repeated in the 1980s and 1990s, particularly in the hands of Edwin Navarro Camaya and Michael Raymon Pangilinan. In 2008, a group of young writers led by Eliver Sicat, John Balatbat, Max Rosales and Bruno Tiotuico formed the Ágúman Súlat Kapampángan so as to promote the teaching and usage of Kulitan.

“A basic Kulitan class and two advanced classes are being taught every month,” Pangilinan said, “at Sínúpan Singsing (Center for Kapampángan Cultural Heritage) at the Angeles City Library & Information Center at the Heritage District in Ángeles City.

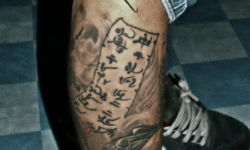

“Currently, Kulitan is still used for heraldry, seals, logos, as well as for titles of public and private events and publications, and also for signatures and private diaries. We hope to remedy the dearth of literature in the near future.”

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General Script, Language, and Culture Resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Kulitan Instructional Video

- Siuala ding Meangubie – Kulitan

- Scriptsource

- Introduction to the Kapampangan Language (PDF)

- Introduction to Kulitan Book

- Kapampangan Dictionary App

Community Resources

- Kulitan Indigenous Kapampangan Script Facebook

- Kulitan: Kapampangan Script Facebook

- Center for Kapampangan Cultural Heritage