Profile

Kayah Li, also called the Kye Bo Kyi script, might be called a defiant alphabet–and, like Hanifi Rohingya, it is also, to a considerable degree, a refugee alphabet.

Refugees live in harsher and more demeaning conditions than most non-refugees know, or can imagine—virtual prisons, in many cases. And as in prisons, anything that shores up identity, individual and collective, is vital.

Piers Kelly writes:

“In March of 1962, a university-educated teacher in Kyebogyi village by the name of Htae Bu Phae spent the night inventing a new script that was to represent and unify the Karen languages of Myanmar. His motive was secular and political: “I thought of the possibility of a special alphabet for the Kayah peoples since my boyhood […] I wanted to show our specificity against the Burman.”

In creating the Kayah Li script he was rejecting three scripts that had been in use by, or had been created for, the Karen people. One was the Burmese script, widely used throughout the region for centuries, but also representative of the authorities in Myanmar–an important fact, as we shall see.

The other two scripts were Western religious imports.

“A Roman orthography for Western Kayah had, by the 1950s, already been introduced by Catholic missionaries into some Catholic schools and the liturgy and in 1962, a Karen Catholic from the town of Hpruso created a Burmese-based script with encouragement from government authorities. A direct derivative of the Baptist orthography for Sgaw Karen, the new Catholic script was used only in Sunday schools, holiday programs and literacy projects. It was likely to have been this script, with its pretensions to Burmese ‘nativeness’, that spurred Htae Bu Phae into action the same year.”

The Karen and Hmong people in particular have a history not only of creating scripts but of cohering and mobilizing around them, moving them from their individual creator to collective property and a source of pride.

“Htae Bu Phae soon began teaching the Kayah Li script in Kyebogyi, and by 1975 it had generated enough interest to justify the formation of Kayah Literature Association, an organisation dedicated both to the promotion of the script and the documentation of local folklore. The following year the separatist Karen National Progressive Party, of which Htae Bu Phae would rise to the rank of General Secretary, proclaimed the script as the official and national alphabet of Kayah State.”

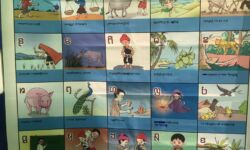

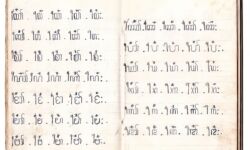

In the 1980s, officials in Kayah state began to print and circulate school books, dictionaries and magazines in the script. Once a script reaches that level of official status, it is usually both stable and secure. The Karen people in Kayah state, though, were about to lose all semblance of stability and security.

In the early 1980s, the Burmese government policy of Four Cuts resulted in the widespread destruction of communities and the decline of traditional cultures. Thousands of villages, especially in the Karen and Karenni States, were burned to the ground, including houses, religious buildings, schools, belongings, and sometimes even domestic animals. In many areas, it became the norm for the villagers to live in constant fear of the Burmese military coming to their village, terrorising the villagers, stealing their food, forcing them to become porters and mine sweepers, raping ethnic women, and torturing and killing anyone suspected of having a connection with the ethnic armed opposition. Whilst some villagers endured the abuse by developing warning systems and repeatedly fleeing to the jungle, others fled their villages for good. Others still had no choice as their village was already in ashes on the ground.

When the first refugees arrived in Thailand in 1984, no one could have predicted that many of them would still be there 30 years later: by the end of 2014 nearly 100,000 had been resettled to third countries, but more than 110,000 were still in the camps.

The script would turn out to serve a different, grimmer purpose than Htae Bu Phae might have imagined: it became a way for the refugees to remember and maintain their sense of identity, individual and collective, under the most difficult of circumstances. Indeed, the literacy and education levels in the camps reached such a level that Karen families in Myanmar crossed the Thai border to have their children educated in the camps.

“Karen and other ethnic peoples of Burma traditionally place a very high value on education and many have crossed the border to Thailand in order to go to a camp school,” reported one NGO. “Although the majority of the camp populations have arrived as a family unit, many parents also send their children to attend schools in refugee camps across the Thai border.”

“The turbulent political context in which the script arose,” Kelly wrote, “is reflected in two alternative labels for Kayah Li writing: ‘rebel literacy’ on account of its origins within a separatist movement, and ‘camp script’ because of its later prevalence in Karen refugee camps. By 2001, a Thai government survey estimated that in the Karen refugee border camps literacy levels in the Kayah Li script were at 48 per cent placing total Kayah Li literacy at around 10,000.”

Just recently, according to Myanmar Indigenous Community Partners, the script has started to appear within Myanmar under a program of indigenous education.

“UNICEF partnered with the Ministry of Education to produce materials for this new initiative. The Local Curriculum is now understood to be a subject 3 days/week ‘ethnic language teaching’ and two days/week ‘local knowledge.’

“it is quite a dramatic change from non-Bamar indigenous languages being illegal to, in theory, being supported.

“Materials were created for 24 groups for the ethnic language teaching portion. Some groups started to implement it in the 2019-2020 school year. There was a lot of confusion as to how it was to be implemented. The government also hasn’t funded the printing of materials, so groups that have started using the Curriculum have done so by their own means.

“There aren’t any schools under the Karenni education system in the country yet so it isn’t being taught too widely outside of maybe some community schools and other informal classes – possibly some church programs. The Language and Culture Committee has been active for quite some time but it was only until relatively recently that they were able to use the Kye Bo Kyi script.”

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General Script, Language, and Culture Resources

- Unicode

- Wikipedia

- Unicode (PDF)

- Article on Karenni Refugee Camp

- Background on Karenni People

- World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Karenni

- Karenni History Blogspot

- Scriptsource

- Kayah Li Bible App

- English – Kayah Li Dictionary (PDF)

- Novel about a Karenni Boy

- Kayah Li Language Lessons (PDF)

- Kayah li Alphabet Song

Community Resources

- Karenni Alphabets Facebook

- Karenni Refugee Support Website

- Karenni Human Rights Organization

- Like We Don’t Exist – Karenni People Documentary