Profile

Authors of writing systems need to be as creative as they are linguistically knowledgeable. A little self-promotion helps, and a lot of perseverance is vital. Of all the script creators we know about, though, nobody was as inventive as Dunging Anak (son of) Gunggu, creator of the Iban Dayak script that now bears his name.The Iban is the largest indigenous group in Malaysia with a population of more than a million, most of whom live in the state of Sarawak. The Iban language is spoken by almost two million people in Malaysia, Brunei and Kalimantan, Indonesia. In Sarawak, the Iban language is a lingua franca in most rural towns among speakers of different ethnic backgrounds.

According to legend, the Iban Dayak once had its own script. In a remarkably common creation-and-loss narrative, the Iban recount that once upon a time, Renggi, their ancestral figure, fled from a great flood carrying a piece of bark containing the Iban alphabet. However, because it was exposed to water, the alphabet recorded on the bark was lost. Renggi then swallowed the bark, it is said, since when the Iban Dayak developed the tradition of telling genealogical and instructive tales by rote memorization.

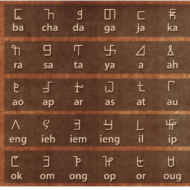

Born in 1904, when education was almost non-existent in rural Sarawak, Dunging taught himself how to read and write Malay and Iban in Latin and Jawi scripts. He invented the first Iban alphabet in 1947, teaching it to his nephews and, briefly, at a local school, but at the time he was better known for other inventions.

By the age of twenty-one, he had already shown his skills in Iban traditional ukir designs, making utensils such as plates and bowls from tapang hardwood, and various Iban traditional musical instruments from wood, bamboo, gourd and palm leaves.

Dunging’s bilik (apartment) of the longhouse was designed and decorated so it looked like a small museum. On the door, Dunging had written, in his own script, ‘Raja Menua Sarawak’ — King of Sarawak.

During one grand festive celebration, Festival of the Departed (Gawai Antu), he cooled this home/gallery/workshop with a fan of his own invention, powered by a bicycle, which was so strong it blew the traditional Iban headgear off the heads of passers-by.

One of his original creations was the rebab musical instrument made out of a coconut shell cut in half. He also made bamboo flutes and created a two-string (out of rattan) wooden nyakun that he played to entertain himself.

He planted his own cotton and spun it into thread, which was used by a substantial number of women weavers around the Rimbas, Layar, Paku and Padeh basins.

He also made hats from the light empalaie wood and the kerupuk palm, which were popular and said to be quite durable and comfortable. He experimented with making hats, trousers and jackets from the bark of the tekalung tree that he flattened by pounding, tailoring the items on himself and walking around as his own model to sell his creations.

Valentine Tawie Salok, a writer with the New Sarawak Tribune, wrote: ‘I remember when encountering him in Sarikei in 1982, he used an orange outfit made out of the tree bark, including the hat. In fact he looked resplendent in the outfit with matching orange tekalung footwear, then possibly one and only pair of such kind in the world.’

Another invention was his own brand of perfume, created by gathering local wildflowers, including wild orchids, boiling them and then filtering the liquid. He enjoyed brisk sales, but ran out of the raw materials and abandoned the project — as he also abandoned his plans to mass-manufacture bicycles made out of local plant materials, which unfortunately turned out to be too bumpy, unsafe and uncomfortable.

More successful were a hydro-powered rice mill he designed and built himself, and his use of the local rubber plantations to invent a laundry mangle (to press water out of newly washed clothes) made of rubber and the hardwood tapang tree. These were lighter and cheaper than the usual metal mangles, and he also donated many to his employees and to the local community.

This colourful context suggests he saw writing — specifically, an indigenously created writing system — as more than a linguistic exercise, but as part of a broader range of efforts to contribute to and improve the lives of those in his community.

His most lasting legacy was his alphabet, though that might have gone the way of the tree-bark outfit, as initial efforts to teach it fizzled out. In 1981, shortly before his death, an Iban-English dictionary compiled by Anthony Richards recognized Dunging’s work. In 1990, Bagat Nunui, Dunging’s adopted son, compiled information about the script in an unpublished book, and in 2001, the Tun Jugah Foundation published an encyclopedia of the Iban Dayak, including Dunging’s alphabet.

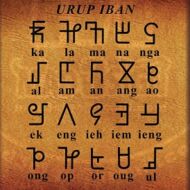

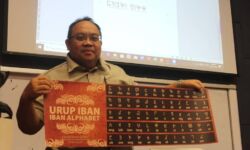

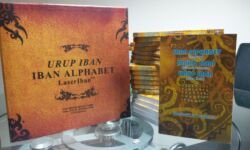

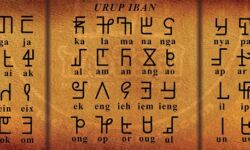

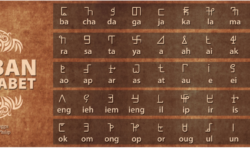

The Malaysian government began to support the teaching of what is now called either Iban Dunging or Iban Dayak, most of Dunging’s creations were then taught to non-Dayak Iban people through universities, schools, and several literacy-related communities. In 2010 Dunging’s grand-nephew, Dr Bromeley Philip, an associate professor of applied linguistics and ethnolinguistics at the Academy of Language Studies, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Sarawak, developed computer fonts for the Iban alphabet, called LaserIban, using which he launched a course called the ‘Training Unto LaserIban System’, or TULIS, Program. (TULIS means ‘writing’ in Iban.)

“The ultimate purpose of the course is to help revive the otherwise disappearing Iban alphabet,” he explained.

Philip is now transliterating three Iban folk tales into the Iban alphabet as part of an effort to transcribe as many Iban language materials as possible. He is also building an Iban alphabet dictionary for use as a reference for the Iban spelling system.

‘Most Iban [whether], old or young, are by now aware that the Iban language has its own alphabet that can be used to accurately translate the Iban’s spoken language into a written language,’ Philip says. He has run Iban alphabet training courses at UiTM Sarawak campus, promoted the script on radio and television, and written Urup Iban, a primer and workbook to teach the alphabet, which he described as “a must-buy item for each and every Iban who loves the language and sense of identity.”

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

Coming soon.