Profile

Eskayan, from the Philippine island of Bohol, is one of the world’s more mysterious writing systems.

The Eskaya, as those who use the Eskayan language and writing system are now known, number about 3000 people living in the villages of Cadapdapan, Biabas, Taytay, Lundag and Canta-ub in southeast Bohol.

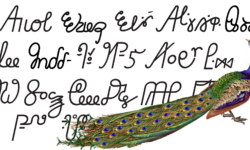

Their script is made up of over 1,000 alphabetic, syllabic and alphasyllabic symbols, and many have additional curlicues that are apparently entirely decorative, even whimsical. Several hundred seem to be superfluous characters that represent sounds that never appear in Eskayan words. The Eskayan language that it is designed to represent is itself a mystery with no clear relationship to other languages in its vicinity.

Eskayan is also one of a number of fascinating scripts that have their own writing-creation myth. Eskayan speakers say the script, and its language, was invented by an ancestral figure called Pinay, who was inspired by the human body. According to the same legend, Eskayan was later carved on wooden tablets and stored in a cave to preserve it from destruction.

The language was then apparently pushed into extinction by Visayan and later Spanish, but then “rediscovered” by Mariano Datahan (ca. 1875–1949), a charismatic rebel leader who founded a utopian indigenous community in southeast Bohol in the aftermath of the Philippine–American War. Datahan used the Eskayan language and script–remarkably, the movement invented not only a script but a new spoken language–as an embodiment and expression of his movement.

According to the Australian linguistic anthropologist Piers Kelly, “Having endured brutal conflict and successive occupations, Datahan’s followers valued the script as an index of an uncorrupted pre-contact civilization free from foreign influence. Living in isolation from lowland town centres, the Eskaya people of the village of Taytay were later ‘discovered’ in 1980 by agricultural advisers. Their script was judged to be so unusual that a number of journalists and amateur anthropologists assumed that the community was an uncontacted indigenous minority.”

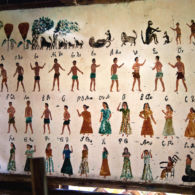

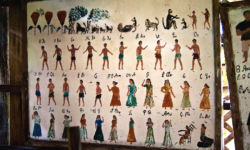

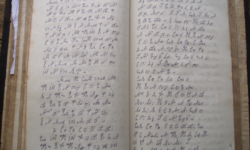

“Acquisition of the Eskayan language and its script,” Kelly explains, “is achieved at volunteer-run schools in Taytay, Biabas and Lundag with classes held every Sunday. Students and teachers begin the day by attending service of the Iglesia Filipina Independiente (Philippine Independent Church), a nationalist denomination that broke away from the Roman Catholic church in the early twentieth century and which maintained the Latin Mass (at least in Bohol) until the 1970s. Straight after the service, classes commence in nearby school buildings referred to as ‘tribal halls’ (using the English terminology). Classes are divided between children and adults and run all day with a break for lunch. Children are taught the rudiments of the Eskaya writing system, while adult classes—which are sometimes conducted exclusively in the Eskayan language—focus on the acquisition of Eskayan vocabulary. Outside the traditional schools, senior women use Eskaya writing in the production of personal prayer books (in both Eskayan and Visayan), and in recent years Eskaya has appeared in the linguistic landscape of Taytay in the form of public signage. The primary domain of use for the writing system is in the reading and recopying of a substantial body of traditional Eskaya literature (also written in both Eskayan and Visayan)….”

Even though the script is not yet fully digitized, numerous handwritten books exist in Eskayan. It is taught in several traditional schools on Bohol and in at least one public school.

“Based on my consultations with Eskaya teachers,” Kelly continues, “I estimate that there are approximately 550 individuals living today who are literate in the Eskaya script, even if this literacy is occasionally assisted with the aid of reference materials.”

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General Script, Language, and Culture Resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Unicode (PDF)

- Article on the Eskayan people

- Scriptsource

- Scholarly Article documenting Eskayan writing system

- Scholarly Article Demystifying the Magic of Eskaya Writing (PDF)

- ParadiseC Repository of Eskayan materials