Profile

Nowadays we have almost forgotten the Greeks in Egypt. We know the Pharaohs and the pyramids; we know the Arabs and Islam; but it’s a telling omission that we tend to assume the one just ran into the other, and the fact we do so says a great deal about the sad fate of the Copts and their language and alphabet.The word “Copt” derives from the Greek word for “Egyptian,” and Greeks have been in Egypt since the seventh century BCE—as visitors, as mercenaries, then, under Alexander the Great, as conquerors. Alexander himself was proclaimed Pharaoh, and established the city-port of Alexandria. One of his generals, Ptolemy, made Alexandria an international center of commerce, art, science, and learning, with the greatest library in the world at the time. The last Pharaoh was a Greek princess named Cleopatra.

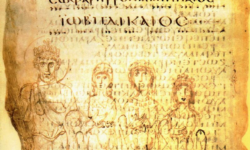

By then, the seeds of the Coptic alphabet had already been sown — a version of the Greek alphabet, with several additional letters from the older Demotic Egyptian script.

Even after the battle of Actium in 31 BCE, when Ptolemaic Egypt fell under Roman rule, Egypt was still extensively settled by Greeks, so it’s hardly surprising that Greek Christianity should reach Egypt early, in the person, according to tradition, of Saint Mark. When the sectarian disputes common in the early Christian Church led to a split between the Coptic Orthodox Church and the Byzantine Orthodox Church, Egyptian Christians wanted a visible symbol of their new faith, and in the third century the Bible was translated into the Coptic language and script. (The astonishing Gnostic codices found at Nag Hammadi were written in Coptic.)

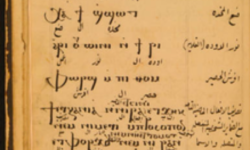

By the year 600, then, the Coptic language was an official language of Egypt, well established in both home and church. It had (and still has) a number of regional variants, but a substantial number of fine manuscripts demonstrated a characteristic and handsome calligraphy. Coptic was even recognized across the border in the three newly-Christian kingdoms of Nubia.

The rise of Islam and the Arab conquest of Egypt began an immediate and steep decline in Coptic fortunes. At times tolerated, at times actively persecuted, the Copts became a religious minority in the twelfth century, and during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries lost a cross-border ally when Nubian Christianity was supplanted by Islam. While still using Coptic as their liturgical language and script, Copts were given little choice but to learn and use Arabic for daily purposes — a situation that still exists today.

In the early twentieth century, Claudius Labib made a determined effort to revive Coptic as a spoken language, teaching Coptic, publishing a Coptic periodical on a printing press he had imported from Germany, and compiling the first five volumes of a Coptic-Arabic dictionary, but he died before it was finished.

Even in the last half-century or so things have deteriorated for the Copts, many of whom were forced to leave Egypt after the Nasser coup of 1952; and the Arab Spring of 2011 led to an increase in religious discrimination and violence against the estimated 6-25 million who remain, according to Human Rights Watch and the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights. In one province alone, 77 sectarian attacks were documented between 2011 and 2017, including abductions and disappearances of Coptic women and girls.

“In Egypt,” wrote one first-hand observer, “there is more than a small discomfort with public expressions of Coptic identity. Churches can not ring their bells. Houses of prayer are sometimes sacked for putting up a cross. Those Copts who achieve public prominence are expected to play down their identity.”

As in neighboring Sudan, though, there are signs of a grassroots movement toward cultural revival. One Coptic nationalist writes: “Coptic Nationalists work for a civilian, secular democratic Egypt for all Egyptians regardless of religion, sex, colour or nationality… We believe that Egypt is formed of three nations, Arabs, Copts and Nuba. We work also for the collective rights of the Copts within a multinational Egypt.”

And though it is rare to see or hear Coptic outside a church setting, during the African soccer tournament in June 2019, a stadium crowd in Cairo displayed a banner, nearly 30 feet wide, in the red, white and black tricolors of the Egyptian flag. On each color band was the same message: “We Love Egypt” in Arabic, English and Coptic.

Update October 2022

In diaspora communities, Copts tend to have more religious freedom but are fewer in number, and cling tightly to symbols of their heritage, language, and religion. The Coptic alphabet can still be seen in Orthodox churches around the world, particularly in the United States, Canada, and Australia. Enthusiasts create online spaces where they can use and spread the language and script. This theme is common for indigenous languages everywhere: while the homeland might be too dangerous or oppressive to conduct language revival, the diaspora in other countries is free to express their culture in speech and writing.

–Grant Li

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General script, language, and culture resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Unicode (PDF)

- Scriptsource

- British Library Coptic Week

- Kellia U.S./German Coptic Research Partnership

- Coptic online translator

- Video of children learning Coptic

- Coptic nationalism

- Coptic Studies Centre

- Research tools in Coptic

- App teaching Coptic letters

- Coptic Reader app