Profile

Vietnam was ruled by the Chinese for over a thousand years, from 111 BC – 938 AD. During this period, the official written language was Classical Chinese, or Chữ-Han.Sometime during the 10th century the Vietnamese adapted the Chinese script to write their own language and called their script Chữ-nôm, or Southern Script.

From the late 13th century, use of Chữ-nôm really started to develop and expand, and it became the script for writing literature and poetry, widely used between the 15th-19th centuries. The Confucian intellectuals recorded folk stories and village entertainment in Chữ-nôm for posterity, while Chữ-han was retained as the script for business, politics, law and formal communication.

In particular, this period saw the flourishing of Việt Nam’s greatest classical poet, Hồ Xuân Hương who, remarkably for her time and culture, was a woman. Though much of her poetry survives, it loses a host of shades of meaning when rendered out of Nôm and into the Latin alphabet.

This heritage is now nearly lost. With the 17th century advent of Quốc Ngữ — the modern Roman-style script — Nôm literacy gradually died out. During the French colonial era it was the Vietnamese intellectuals who exploited Quốc Ngữ to the full and in 1908 the Royal Court in Hue created the Ministry of Education which incorporated Quốc Ngữ into the curriculum. In 1919 it was declared the national script and replaced both Chữ-han and Chữ-nôm.

Today, fewer than 100 scholars worldwide can read Chữ-nôm. In other words, approximately 1,000 years of Vietnamese cultural history is recorded in a system that now almost no Vietnamese can read.

In 1970 the Chữ-nôm Institute was established in Hanoi to find, store, translate, publish the Chữ-nôm heritage. To date it has collected 20,000 ancient books, most written in Chữ-nôm.

Courses in the Chữ-nôm script were available at Ho Chi Minh University until 1993, and the script is still studied and taught at the Han-Nôm Institute in Hanoi, which has recently published a dictionary of all the Chữ-nôm characters. Nevertheless, much of Việt Nam’s vast, written history is, in effect, inaccessible to the 80 million speakers of the language.

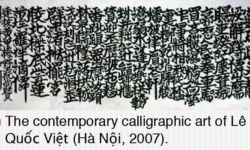

In one area, though, the country’s cultural history still comes together through writing. In the Classical Chinese period and the Chữ-nôm era, Vietnam saw a strong tradition of calligraphy, and over time Vietnam developed a unique style of calligraphy called Nam tự–used first by the bureaucracy, but later for all writing purposes.

The custom of Hán and Nôm calligraphy during New Year still exists in north Vietnam, where Hanoi’s Temple of Confucius hosts calligraphers of Latin, Hán, and Nôm and invites them to showcase their works.

And the script has recently been standardized, with multiple fonts now available here.

Postscript.

Here’s a flashback to 2012:

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.