Profile

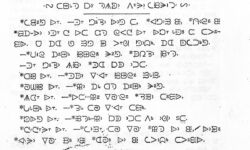

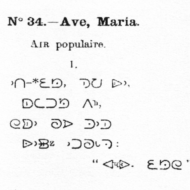

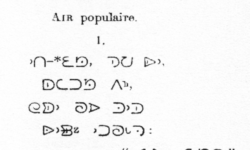

The Carrier or Déné syllabics (known in Carrier as Dulkw’ahke, meaning “toad feet”) were created around 1885 by Father Adrien-Gabriel Morice for the Carrier language, inspired by Cree syllabics.The Dakelh people once enjoyed extensive literacy with the script, but as with other native North American scripts and languages, it became the victim of discriminatory policies — and technologies. It was often used to write messages on trees, and Morice published a newspaper in syllabics which was in print from 1891 to 1894, but usage began to die out in the 1920s when Lejac residential school was opened. That meant that the children ceased to spend the winter, when syllabics were traditionally taught, with their families. For a brief period syllabics were actually taught at Lejac so that the children could read the Prayerbook (although they were punished for using Carrier for any other purpose), but that ceased by 1938 when the bishop made Father Morice produce a Roman version of the Prayerbook, which replaced the syllabic version.

Hardly anyone is actually literate in syllabics today. People ceased to learn to read and write in Carrier in the 1930s, with the exception of learning to read the Prayerbook in Morice’s roman system), until evangelical missionaries developed the current Roman system in the 1960s. Perhaps the last person to have learned the syllabics from older users was the late Mac Squinas of the Ulkatcho band, who died in his eighties about 25 years ago.

Here as elsewhere, the Roman system profited from the fact that it could be typed on an ordinary English typewriter, whereas the syllabics could not be typed and could not easily be printed.

The combination of these factors has led to the current plight, where very few people both speak Carrier fluently and read and write the syllabics.

Kevin King of Typotheque writes: “There are very few people in the Carrier community that use the syllabics on a daily basis at this time, with only Francois Prince, Dennis Cumberland, and a few others using them regularly in their day-to-day life. However, Francois and Dennis are actively teaching the syllabics in the community, and they are starting to experience a resurgence. The technical barriers at the Unicode level were preventing community members from using them on a daily basis though, and now that this is resolved, it should help their use grow, but it will take some time.”

The syllabics have experienced a resurgence of sorts in the form of increased interest in learning about them and increased use in artwork and tattoos. They are taught by Francois Prince and Dennis Cumberland in some schools and communities and by Bill Poser, who has published a textbook, Introduction to the Carrier Syllabics, as part of university-level language classes.

Carrier also demonstrates how complicated the survival and usage of scripts is, and how passionately different portions of a language community may champion different versions of a script, or even entirely different scripts. The Carrier community is not only divided over whether the syllabics should be revived, but even those who prefer writing in a romanized script differ over which version to use. In some respects this debate is linguistic, in the sense that a script should fully and accurately represent the sounds of its spoken language; but it also demonstrates how iconic the graphic elements of a script become to its users, how deeply rooted in both collective and individual usage and history, how strongly the sign represents the self.

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General script, language, and culture resources

Gallery