Profile

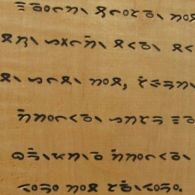

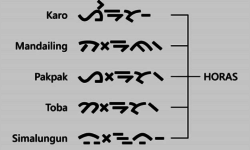

Aksara Batak, or Batak writing, is a group of scripts used to write the Batak languages of North Sumatra, Indonesia: a southern group of Toba Batak, Mandailing and Angkola, a northern group consists of Karo and Pakpak-Dairi, and Simalungun, an early offshoot from the southern group.

Batak writing grew out of the Pallava script, a writing system in South India at least as early as the fourth century AD. By the 1700s Batak writing had already developed into a number of regional variants—not surprisingly, as each Batak language is spoken by groups of people with distinct histories, social organization, and ethnic identities: while Toba Bataks use the word “Batak” to refer to themselves, for example, other groups reject the label, preferring, for example, orang Mandailing (“Mandailing people”) or orang Simalungun (“Simalungun people”).

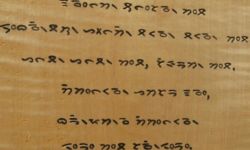

Each surat, or script, consists of nineteen to twenty-one radicals called ina ni surat, or “mother of the script,” and six to eight diacritical marks called anak ni surat, or “children of the script.” “Mother” and “child” in these cases stand in for “big” and “small,” and these big and small letters combine to form syllables. Each big letter represents a consonant and an inherent a vowel, and small letters are written next to a big letter to change the vowel.

Anyone in Batak society, wealthy or poor, could learn to write, and young men in particular wrote love letters. A German visitor observed in 1847:

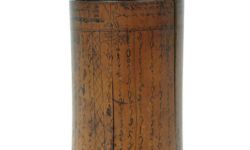

“The children are not instructed in anything and the only thing they learn by imitation is writing, that is, scratching characters with the point of their knife onto bamboo and reading what was thus written down. This art of written communication is the only scientific art which they have; it is, however, widespread among them, especially in [Toba], where young men scarcely fourteen years old usually begin their first literary efforts by sending love letters to young girls, scratched on pieces of bamboo….”

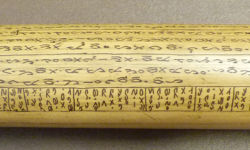

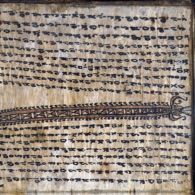

Traditionally, Batak script was written on bamboo, water buffalo bones, or the bark of the Aquilaria tree. In the first two cases, the writing was incised using the point of a knife, and then soot was rubbed into the cut letters so they could be read more easily.

Early Batak writing was interesting in many ways, one of which was that it included an entire genre of threatening letters. The writer would write his demands on a short piece of bamboo, and accompany it with tiny bamboo weapons to drive home the point—rifles, spears and lances, for example, or a flint, which meant, in the case of European plantation owners, “I’m going to burn your tobacco barns down.”

Writing on bamboo tubes and buffalo bones included proverbs and sayings, called umpama and umpasa, and lamentations used during funeral-rites, called hata ni andung.

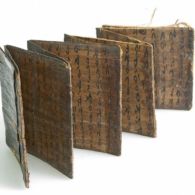

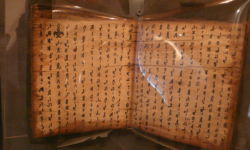

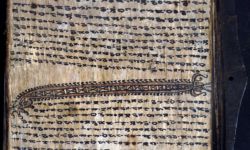

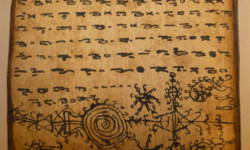

Perhaps the most famous media were books made of folded bark called pustaha. According to Batak mythology, there was once a bark book (called Tumbaga Holing) so rich and compendious it held all the knowledge possessed by humankind—but many Batak believe the Dutch stole this marvelous book and took it back to Holland.

Composing a pustaha was a specialized skill, obtained only through apprenticeship with datu, a hereditary occupation in Batak societies that is translated variously as “priests,” “magicians,” “healers,” “shamans,” or “ritual specialists.”

The ink alone, of resin soot and tree sap, had its own spiritual potency and took considerable care to make, as one pustaha directs: “When the oil is added to the other ingredients, the following signs should be observed…. If the oil separates out in the middle, this is a bad omen. There will be unrest. Since this is unavoidable, one should stop the preparation of the ink.”

In addition to the materials, the datu needed to know the hata poda, or secret language of instruction, a variety of Batak language that used a sizable vocabulary of esoterica derived from a mix of sources, including words of Malayan and Sanskritic origins. Pupils learned this language through apprenticeship to datu, and its use accompanied events ranging from the rituals at the founding of a new village to ceremonies accompanying the birth, marriage, and funerals of individuals.

As with other shamanic scripts, the writing in the pustaha was not intended to be read word by word, or even understood by the uninitiated: it served more as a means of passing on knowledge from each datu to his pupils. Not surprisingly, then, each datu wrote in an individual and subjective way, sometimes using characters from several different Batak regions—making the text even harder for the uninitiated to understand.

This shamanic tradition declined in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as large groups of Bataks converted to Islam and Christianity. Missionaries saw the Batak writings as being all too similar to the magic books of the Jews and the Greeks and thus, in the words of one missionary, “ripe to be burned.”

Yet the missionaries supported the script, if not the literature, recognizing the Batak language and its script as vital to the culture. They created typefaces and printed a variety of books in Batak until the end of World War I. When they stopped, it was partly for financial reasons, and partly for a reason all too common in colonized cultures: the traditional writing system had come to seem insufficiently sophisticated compared to that of the Eurpeans.

The Batak script is now to some extent used for display and decorative purposes, in the signage of shops and governmental institutions, and on street signs, and more generally on tourist items, including miniature Batak calendars, pustaha, and clothing such as T- shirts. It is taught a little in North Sumatran elementary schools as a feature of Batak heritage, as a cultural artifact rather than as a day-to-day writing system for spoken Batak language, for which the Latin alphabet is generally used (as it is for Indonesian, the national language).

As of 2020, several font packages are available for use on Windows, Linux and Macintosh operating systems. This has made the teaching and writing of Batak script easier for students of Batak language, and institutions of higher education in North Sumatra such as the University of North Sumatra incorporate regional Batak language and literature into their curricula.

Updated August 2020.

Joshua Lieto contributed to this profile.

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General script, language, and culture resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Unicode (PDF)

- Scriptsource

- Indonesian literature — history, humour and language

Community support

- Facebook Group

- Indonesian Language Program at University of Hawaii

- Research on the Batak script

- A Grammar of Toba Batak

- Aksara Batak: Variasi, Angka, dan Aksara “Persatuan”

Font and keyboard resources

Gallery