Profile

Creating a new script for an indigenous people during a colonial era is a two-edged sword.

The desire to claim and assert one’s cultural identity may provide the driving force that sustains an author through the long, hard work of creating a writing system, and it may also be the force that makes the resulting script popular. The colonial authorities, though, may well not want their subjects to develop a sense of their identity and self-respect, and in that sense, the more successful an indigenous script is, the more dangerous it may be.

One of the most remarkable of these creations, the Bamum alphabet, fell prey to its own success.

Piers Kelly writes: “Shortly after the German colony of Kamerun was proclaimed in 1884, the Kingdom of Bamum in the northwest of the colony suffered a crisis as the monarch was assassinated at the hands of his brothers. A civil war ensued before the heir, Ibrahim Mbouombouo Njoya, came of age to assume the throne. Njoya’s kingdom, centring on the town of Fumban in the northwest of the nation, was by then recovering from war with the Nso people and the king’s new allegiance to the Imperial German Government helped to shore up his legitimacy in a court divided by intrigues.

“The illiterate King Njoya was inspired to create writing after a revelatory dream. In Njoya’s retelling, a teacher instructed him to draw an image of a hand on a wooden tablet before washing it off and drinking the water. The imagery is telling. In many regions of Africa a well-established healing ritual involves writing Quranic versus on wooden slabs or plates that are then washed off with water to be consumed by the patient. These rites do not require the participants to be literate in the Arabic script: it is the body itself that must read the sacred text without interference. Possibly the dream prompted Njoya to discover a ‘literacy’ latent within his body that would find expression through his writing hand. Such rituals were sufficiently familiar in West Africa outside of Muslim communities that the Christian inventor of the unrelated Medefaidrin script had a similar inspirational vision which led him to believe that by drinking water he would “receive knowledge washed from a great book written in different colored inks and thus receive the words of God.”

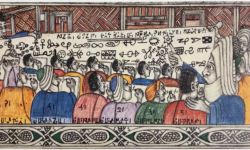

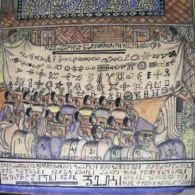

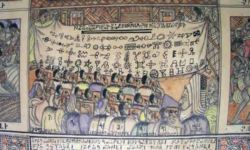

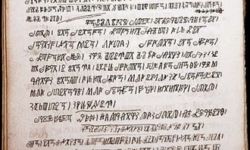

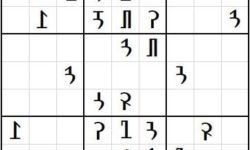

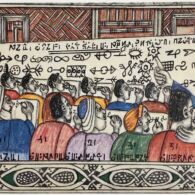

“Upon awaking, Njoya re-enacted the dreamed ritual before beginning work on a syllabary for his native language of Bamum. With assistance from at least two royal advisors, he drafted over 1000 pictographic charac- ters that were intended, at first, to represent objects and actions. Progress was slow and there were several abortive attempts before Njoya and his team began experimenting with rebus writing and narrowed their attention to indi- vidual syllables. In a first practical draft, the working group completed a table of 465 syllabic characters of largely pictographic inspiration, and a single semantic determinative was introduced to differentiate homonyms. Over the next fourteen years, the script went through six revisions, becoming progressively smaller with each draft. The total inventory of characters was reduced successively from 465, to 437, to 381, to 295 and 205 until it stabilised at 80 characters in 1910. At the same time, Bamum transitioned from a logography to a logosyllabary to a syllabary and finally to an alphasyllabary. The graphic form of the characters themselves became marginally simpler.

“Njoya’s collaborative creativity was not limited to the art of writing and he is also remembered for devising a secret courtly language. Assisted by a female European missionary, the pair generated a lexicon from nativised French, German and English words with reassigned Bamum glosses. Njoya employed the Bamum script to produce a corpus of manuscripts in both the Bamum language and the restricted courtly language.”

Using this script, called a-ka-u-ku after its first four characters, he wrote a history of his people, a pharmacopoeia, a calendar, maps, records, legal codes and a guide to good sex. He built schools, a printing press and libraries; he supported artists and intellectuals. This seems to have been all well and good in the eyes of the local colonial power while Cameroon was under German control, but when the French took over part of the country after the German defeat in World War I, they maneuvred Njoya out of power, smashed his printing press, burned his libraries and books, tossed out sacred Bamum artifacts and sent him into exile, where he died.

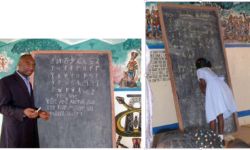

It’s a sign of how important an indigenously created script can be that despite Njoya’s death and the almost complete suppression of the a-ka-u-ku syllabary, his son and grandson held on to the script as a cultural symbol. In 2022 the Endangered Alphabets Project initiated a collaboration with King Njoya’s great-grandson and the Bamum Scripts and Archives Project to help begin the process of revitalizing the Bamum script.

–Edited and updated by Eddie Tolmie

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General script, language, and culture resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Unicode (PDF)

- Scriptsource

- Bamum Language Resource

- Learn the Bamum Language

- Article explaining origins of Bamum script

Community support

- Bamum Scripts and Archives Project

- Royaume Bamoun

- Bamum: Visions of Africa Series

- Article about the Bamum script and archives project

Font and keyboard resources

Gallery